Reverie

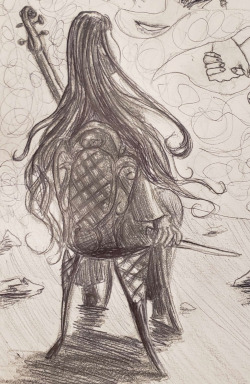

My fingers gripped the bow improperly, grazing across the ebony, the pernambuco, the white horsehair. I looked, almost listlessly, at my other hand, my left hand, which held the neck of the cello. The metal strings seemed to vibrate on their own, as if reaching for a purpose they found impossible. No sound came. My bow drifted through open air.

Above me, the void flashed and churned.

I heard a noise, like the beat of a single distant drum. I turned, my breath catching in my chest, but saw nothing. Nothing more than the endless gray landscape I had come to, an infinite flat plain of stone, containing only lifeless happenstance rocks to mark the distance.

I wondered if perhaps I had always been here. Maybe this was just what the world looked like, once all illusions had been swept away.

Maybe I’d always been silent.

My thoughts felt slow and detached. What was this place? How had I arrived? How, and why, had my cello come with me? I hadn’t played in years. I didn’t see the point anymore, and the music wouldn’t come.

The sky was filled with stories, and some of them were mine. The void flashed with images from the life I’d led, and, perhaps even more painfully, from lives I couldn’t recognize…

I looked into one such flash as it came, and I found myself remembering in perfect detail, as if it was all happening again.

—FLASH—

The phone rang. Gustosi.

“Hey, Octavia!” came his voice from the other end of the line. “It’s been so long! I just thought I’d check in. How are you doing?”

“I’m…getting by,” I managed.

“Great, great! Everything going well with your family?”

I sighed. “Not really, actually.”

“Oh no, what’s wrong?”

“Well, my father’s still dead, my mother’s still crazy and my brother is still sick.”

“Oh, right, right, yeah, that’s uh…yeah, I don’t know what to say. But uh, you know, things are going pretty well on my end!”

“Oh, are they?”

“Yeah, yeah, you know, me and my wife Gloria, we’re going to the art fair on Friday. Just a little art fair, you know, we thought that sounded nice.”

“It sounds lovely.”

“Yeah, so, you know, my brother just got a new job at the library. He’s doing well. He likes it.”

“I’m glad for him.”

“How’s your job going? You doing ok?”

“I…” I struggled for words, “...I’m managing. It’s a job. It’s part-time. I serve coffee. It’s not exactly a dream job.”

“Oh well, you know, that’ll lead you places. You know, just keep at it.”

“I’m thirty-five, Gustosi. I’m thirty-five and I work part-time because I’m too traumatized to do anything else.”

Mother always used to hide our failures, so I’ve made a habit of bringing them up. Not that it’s made much difference.

“Oh, right, yeah…the, uh, the stress disorder.”

“Complex PTSD, actually.”

“Yeah, yeah…uh, are you seeing a therapist?”

My tone grew a little sharper. “Gustosi, I’ve been seeing therapists since before I met you. Which was twelve years ago.”

“Right, I remember now, yeah…uh…has it helped?”

I sighed again. “Yes, a little. There have been a lot of therapists, some good, some bad. Usually it helps. But I’m…I’m still in a lot of pain, Gustosi. I still sleep till noon everyday.”

“Oh, well, uh…you know, just keep hanging in there. Let me know if you want to talk.”

What the hell would you even say? “Thanks.”

“Have you tried journaling? You know, like, I have a gratitude journal and it really helps me.”

“I will…let you know about that.”

“Ok, good, good! Glad we got to talk. I’ll talk to you later, ok?”

“Goodbye.”

I hung up.

—FLASH—

I was nine years old, seated at the kitchen table with my family.

“It’s Sunday evening,” I said, apropos of nothing. “There’s always a bad feeling on Sunday evening.”

“Why?” asked my mother with an expression of concern.

“Because I’ve got school tomorrow,” I explained.

Somehow, the conversation came to an immediate halt.

—FLASH—

I was nine years old, boiling alive.

I wanted to play. I wanted to play so dearly I could hardly think of anything else. I’d spent the whole day at school thinking back to the precious little ¼ cello my mother had purchased for me. I’d walked through hallways with classical music in my head. Bach, of course, and Brahams, but more than that. I’d been writing pieces in my head, marking out notes on the edges of my papers, hoping that I would be able to read the music later without a proper staff or a key signature to guide me.

Now those papers were stacked in a neat corner at the edge of my desk in my bedroom. I sat on the chair, a blank worksheet in front of me. I glanced at the music, then forced myself back to the worksheet. They wanted me to do math. I got up to get a glass of water from the kitchen, passing my father along the way.

“How’s your homework going?” he said.

“I’m working on it,” I said hurriedly, then went back up the stairs to my room. The homework was still there, as was the cello.

The cello. The cello! My beautiful cello! I’d made her sing when I’d first brought her home last week, feeling the vibrations through my fingers, not even caring that I didn’t know the notes yet. There was something about the sound that transported me, making me feel that the world had suddenly been infused with a kind of magic. There was something more to the world, then. Something that connected me to half a millennium of history, and to an indescribable future.

When I played my cello, I didn’t hear her voice alone. I heard the entire orchestra in my mind, the soft violas and the stately timpani, an elegant french horn, like a swan, alongside a pompous and slightly silly bassoon, bright shining trumpets, even a playful saxophone (who says an orchestra can’t have one?)...all in harmony with me, with the melodious voice of my cello.

But she had no voice now. She sat in the corner of my room and I tried, I tried not to look at her. I forced myself to sit in my chair and stared down at the math homework.

I found my fingers holding an imaginary bow.

I leapt up from the desk with a start, briefly worried that the noise might have alerted my father. That he (or Mother) might come to check on me, might wonder why I hadn’t finished yet, why I wasn’t good enough.

I shouted inside my mind. Why don’t you just DO THE WORK?! You want to play cello, so just do your homework! You can play when you’re done! I couldn’t fathom my own pig-headedness, my own stubborn viciousness. I needed to do the work, obviously! It was homework! It was necessary! The thought of how my parents would feel, how they would look at me if I missed an assignment, was unbearable.

I was nine years old, but I already knew that there was no greater glory than homework. My mother had made it clear.

Not long ago, I’d received an F for a missed assignment. I’d holed myself up in my room thereafter and looked up “F” in the dictionary to better immerse myself in my shame. My parents had sat me down afterwards in the living room. My father had intoned in a solemn voice: “In the Melody Family, we only get A’s and B’s.”

I looked over my shoulder at the cello. My darling cello! I couldn’t practice now; they’d hear me! Someone would come by to ask if I’d finished my homework! How could I have not done my homework already? It’s easy, Octavia! You stupid brat!

I found myself getting distracted by every little thing, and I grew afraid of my inability to pay attention to the one thing that actually mattered. I fantasized of a room without distractions, a great ceaseless void with just me and a desk and my math homework because that’s what matters. THAT’S WHAT MATTERS, OCTAVIA!

I stood and grabbed the windowsill next to my desk. I reared my head back and threw myself at the windowsill, intending to pull back at the last second, intending a symbolic gesture of shame.

I missed my mark. My forehead impacted against the hard edge.

Wincing, I put my hand along the spot where I’d been hit. I nearly cried.

I heard my father’s voice through the door. “What was that?”

I sat down at the desk. “Nothing. Just slipped.”

He opened the door. “How’s your homework coming along?”

I stared at him for a bit too long. “It’s…fine, Father.”

He moved to leave, but I interrupted him. “Father?”

He paused. I swallowed.

“I was thinking I might…perhaps I should put the cello somewhere else until I’m finished. So I’m not distracted, I mean.”

He nodded. Without a word, he took the cello and carried it out of the room.

I nearly cried.

—FLASH—

I was eleven years old, in my bedroom. It was actually a new room from two years prior, as we’d rearranged the house somewhat.

My younger brother was on the other side of the door, screaming and pounding his fists against it.

I sat there in total calm, thinking distantly of how strange it was. He was just like this, always shouting, always the hair-trigger temper. He was mad at me for some unfathomable reason. I didn’t feel threatened, though. He didn’t bother trying to open the door. He just screamed and pounded at it, and I thought to myself that I was quite mature to be able to endure this with such serenity.

—FLASH—

“Where were your parents?”

I was twenty-eight, seeing a therapist on my own. I was surprised at the question.

I flattened my skirt. “What do you mean?”

“Your brother was having a tantrum, banging at your door. How long did this continue?”

“Twenty minutes, I suppose?”

She looked at me with concern in her eyes. “Where were your parents?” she repeated.

“I…I don’t know.” The question had never occurred to me.

“You didn’t think about it at the time?”

“No. It was my duty.”

“Your duty?”

“Yes.”

“What was your duty?”

“I had to…to deal with him.”

“What do you mean?”

“Whenever he got upset, I…I was the one who had to calm him down. I got quite good at it!”

“He was screaming and pounding on your door.”

“Yes, well…it could have been worse.”

“Where were your parents?”

“Where were they supposed to be?!”

“In the hallway with him! He was upset about something, obviously. They must have heard him. They didn’t do anything to help?”

I began to feel my own heartbeat in my chest. “Why should they?”

“They were the parents, Octavia. They were supposed to help.”

I shook my head. “No, no, it was my job. I was the one to handle those things.”

She looked at me for a long moment. “What would have happened if you didn’t handle it?”

I paused. “They would have….freaked out, I suppose.”

She waited. I continued. “I remember one time my father was so angry at him that he…he took his toys to the woods. We–we had some woods next to the house and I remember he grabbed my brother’s, oh, I think it was a stuffed bear or something, and he threw it out there. Focoso was bawling about this bear, and Father shouted ‘IT’S IN THE WOODS!’”

“How did that make you feel?”

“I suppose I…I must have felt rather afraid.”

“And then you looked out for Focoso after that.”

“Well, not at that instant. I just, sooner or later, it was just…my job.”

She leaned in. “Did you ever throw your brother’s toys into the woods?”

I shook my head. “Never.”

—FLASH—

I was fourteen years old, and my family played a board game at the kitchen table. It was so refreshingly normal, so calm and content. Focoso made jokes now and then, or quoted movies we’d seen together, and everyone laughed and smiled. Anyone would have looked at us and said, “That’s a healthy family.”

—FLASH—

I was fourteen years old, in my bedroom. High school had been ripping me to pieces, but right now I didn’t have time to think about it.

My father was screaming at Focoso again.

It had been going on for an hour now. Focoso and Father’s voices collided in sheer cacophony, cascading into my room from down the hall. My cello sat in the corner, unused for the last month. I trembled.

My father’s voice rose above the din. “YOU WANT RAGE?! I’LL GIVE YOU RAGE!”

I fumbled for the phone. My friend Lyra lived about 20 minutes away. I called her house.

“Hello?” said her father.

My parents had taught me a protocol for these things. It went: “Hello, is the [name] residence? This is Octavia Melody, may I speak to [name] please?”

For once I dropped the protocol. “Hello? Mr. Heartstrings? This is Octavia. I…need your help.”

“Oh sure, Octavia. What’s the matter?”

The shouting died down. Apparently Focoso had stormed out of the room.

I began to cry. “Can I…stay at your house tonight?”

“What?”

I sobbed. “My father is angry, and I don’t want to, I don’t want to stay…”

“Oh, hey, hey there, calm down. It’ll be ok. May I speak with your father?”

I nodded. “Sure. Let me get him.”

I took the phone into my parents’ room. They saw my tears and appeared to be concerned for me. I handed the phone to my father. “Mr. Heartstrings wants to talk to you.”

I waited outside the door, leaning up against it, my hands on my knees. The door opened, and my father handed me the phone.

“Octavia?” said Mr. Heartstrings.

“Yes?”

“I think you’re gonna be alright. You let me know if you need anything.”

I nodded dumbly. “Alright.”

The line went dead. I looked up at my father.

“Just so you know,” he said, apparently quite gentle now, “I wasn’t anywhere near violence.”

He closed the door.

—FLASH—

I was fifteen. I watched as my parents methodically removed the hinges from Focoso’s bedroom door. They took the door from its frame and placed it along the wall in the hallway. They put up a flimsy curtain so that Focoso could change his clothes in privacy.

The door had been removed so that Focoso would no longer be able to escape from them.

I didn’t mention it to anyone.

—FLASH—

In chemistry class, I sat by the window. The teacher often left the window slightly open, and I felt the air that flowed through it. It was so different from the air of the classroom. A free air. A pure air. Unbounded.

Sometimes the breeze carried a tune, even. My high school orchestra practiced on the other side of the courtyard.

It lifted my spirits, except when it crushed them.

I turned back to focus on chemistry.

—FLASH—

I was sixteen years old, at my desk in my bedroom. I was journaling.

“I feel my soul is on a leash,” I wrote, “a longer leash than others have, I’m sure, but a leash regardless. I haven’t played cello more than a handful of times in the last year, and never with an audience. I still want to play. I even dream of it. Sometimes I imagine what it would be like to wake up somewhere else, somewhere all alone, or with new people who understand.

“I can’t express my pain. I can’t understand it. I went to the school counselor and told her how stressed I’ve been. She said, ‘Sometimes stress is a good thing and sometimes it’s a bad thing.’”

I paused. I wrote: “I don’t think she has any answers for me.”

The next day I went back to the journal and made another entry: “But of course I have to understand that my parents know best. They’ve lived in the adult world and they know what I need. I have to get these grades so I can be successful in life. Cello will have to wait.”

—FLASH—

I was sixteen years old, seated at a lunch table in high school. I reached into my backpack and took out the take-home test we’d been given in AP Physics. I started working on it.

A voice came from the side. “Octy!”

I looked up to see my friend Rara bounding towards me, skipping along in defiance of gravity. “I did it!” she beamed.

“You got in?”

“First Soprano! I’m getting a solo!” She flung her arms around me.

I hugged her in turn. “I…I’m glad for you.”

—FLASH—

I was seventeen years old, in the lunch room again. Everything was fine. As far as I knew.

I was a senior, and I felt that I’d finally gotten used to the schedule. Sure, I had three AP classes and a job at the library, but I told myself that it wasn’t as bad as junior year, that I’d learned coping skills, and that everything was bound to work out. Only a few months left to go before graduation.

I stood up from the table, hoping to buy something at the counter, when a wave of dizziness swept over me. I faltered. I began to walk, but the feeling did not pass.

An hour later I was in AP Government, huddled awkwardly over my desk. (I didn't know it yet, but my posture was helping to stabilize my head, which minimized the awful feeling.) A friend said I should see the nurse, and I finally excused myself.

Entering the nurse’s office, I still had no idea what I was bound for.

“Excuse me? I’ve been feeling dizzy and I was wondering what I should do about it?”

The nurse motioned for me to sit. “When did it start?”

“About an hour ago.”

“Let me get you some water and we’ll see how you feel.”

I took the cold water in my hand and drank it down. Suddenly my whole body began to tremble, as if I were outside in the middle of winter.

The nurse took notice of my hands, which grew sickly white before my eyes.

“Maybe you should go home.”

—FLASH—

I was seventeen, and it had been two months since the Stress Disorder first took hold of me. Every motion, every exertion, risked vertigo and heart palpitations. I sat on a chair in the kitchen, feeling slightly hungry. I spied a bunch of bananas on the counter across the room, but I didn’t rise. It wasn’t worth it yet to eat the bananas; the effort of getting them was worth more than my hunger. I waited, doing the cost-benefit analysis in my head, waiting for the exact moment when my hunger became severe enough to warrant the effort.

—FLASH—

I was seventeen, lying in my bed, missing another day of school.

I’d long since learned to keep food and water on my bedside table. There was no way of knowing when I might wake up to find myself paralyzed with dizziness. Sometimes it was too much even to turn my head to the side to see the food. I would simply stare at the ceiling and reach over blindly until I found a banana or a granola bar or whatever else I’d laid there. Keeping my head perfectly still, I would maneuver the food into my mouth, and then the water.

The doctors had not found anything wrong with me. The nurses, the ER doctor (when I had chest pains), the family doctor, the walk-in clinic. The endocrinologist was next. Maybe she would have something.

Mother came in, awkwardly. “Do you think you’ll be able to go to school tomorrow?”

—FLASH—

After several days of tests, the endocrinologist looked at me. “Maybe you’re just really stressed.”

—FLASH—

I was nineteen years old, secluded in a garden at my college. I was weeping, silently screaming about my pain, my bewilderment. I came here often, in between going to classes and acting normal.

It never occurred to me that I ought to see a therapist. I’d long since learned not to rely on anyone.

—FLASH—

I was twenty-six years old, and my father lay dying of cancer.

I’d worked so hard to help him. I’d memorized his med schedules, which were ever-changing on account of his pain. I’d researched new techniques and mentioned them at doctor’s visits. More than once, professionals had asked me if I was studying to be a nurse myself. “No,” I always said, “I’ve just been searching the internet for the last six months.”

I went home from the hospice after dinner, leaving my aunt to care for him. I went to my room — I had never properly moved out — and sat in the darkness for a while. My full-size cello lay in the closet, untouched.

I wondered if perhaps the last thing my father would ever say was that he was disappointed in me.

I lay down on my bed, to keep the dizziness at bay.

—FLASH—

I drove my mother to the insane asylum. Or the “treatment center”, or whatever they call it these days.

In retrospect, she’d always been a little crazy. I guess it grew worse after my father’s passing, when he wasn’t around to steady her. It was almost poignant, except that she’d cheated on him. Both before cancer, and also during cancer.

I had discovered it, and kept it a secret. It was my duty, was it not?

A few months after father passed she’d fallen for some foolhardy scam online. She attempted to swindle me and everyone she knew in pursuit of boxes of gold that never came. Then she threatened me. Then she became suicidal. And then she agreed to go to the asylum. So I drove her.

I suppose it’s possible that I saved her life. She stayed there for two weeks, before they sent her home. She reached out to the scammers less than an hour later, still intent on her boxes of gold.

It was another year or two before I cut her off altogether.

—FLASH—

The years went by. The old pain haunted me. I kept trying to find some stability, kept hoping for a new dawn, a new chapter in my life. But instead I simply kept myself alive while my father’s inheritance was slowly whittled away.

—FLASH—

I was thirty-one, walking down the street in downtown Canterlot. I saw a girl, a busker of some sort, playing a song with a little band on the street.

She had blue hair in two tones, and purple sunglasses. She seemed…unfathomably alive. She was playing with some sort of sound board, which was connected to the other players’ instruments. I’d heard of audio engineers before, but this was something else! A proper DJ, I supposed. Wearing a crop top that exposed a slender stomach, she seemed to radiate sheer vitality, bouncing double-time to the beat, switching sound controls, talking and laughing with passers-by, improvising, dancing, shining.

Her smile was electric. I found myself drawn to her.

I approached, and one of her friends handed me a flyer. It was for a concert of some sort, which they were evidently here to advertise. The blue-haired girl featured prominently on the flyer. I stared at it for a while, admiring the resemblance. Then I looked at the actual girl, and she looked at me, and our eyes met for far too long before I suddenly turned away, hiding my grin.

The next day I realized that I’d lost the flyer. I have no idea where it went. I often lose things. When you’ve been through hell (as my therapist puts it), it’s often quite difficult to think straight.

Sometimes I wonder what would have happened if she and I had truly met. Would she have liked me? Would we have seen each other again? And again?

Could we have been a couple? Could we have had warm embraces, and passionate kisses? Could we have moved in together, and started a new life? Could she have made me feel safe, after all I’d been through? Would she have held me when I cried, and taught me how to laugh again?

It’s so hard to know. One small thing can make all the difference in the world.

I don’t know. I don’t know anything.

—FLASH—

—FLASH—

—FLASH—

The void flashed and churned.

A dozen more memories passed through me as I sat on a chair on an infinite plane of stone, the bow in one hand, the cello in the other. There was too much to take in, too much to comprehend or describe, and yet I felt I had no choice. I let it all pass through me, flowing like water, passing through and away to some unknowable destiny.

I looked down upon myself. “What can I do?” I whispered.

I sat there for a long time, fighting back tears. The void churned above me. The silence echoed around me.

I spoke to the emptiness. “Does anyone understand?”

Far above me, the void suddenly twitched, as if in response. I looked up, gazing intensely. I wondered. These were all the stories of all that had ever been. They were filled with the heart of humanity, both the memories and the fantasies. Countless lives had contributed to the firmament, whether they knew it or not.

Were the stories themselves somehow aware of the audience? Had we given them life, in some small distant way?

I looked up into the vastness.

“Do you understand?” I whispered again.

Slowly, the images changed themselves. A girl appeared in the sky. She wore a dark red beret and stood upon a small stage at a microphone. Purple hair covered one of her eyes, and the other eye gazed at me intently. When she spoke, her raspy voice seemed to fill all time and space.

She recited a poem, and I knew that she had written it:

The sun is not for all of us

For some it does not rise

Or rises late, and quickly sinks

Beyond the lonely skies

For some there is no warmth today

Despite the words of men

Who measure in a formal way

And know not what they ken

For some their eyes see only dark

Though light be all around

Their hearts are lost inside the night

The path they have not found

They cannot see, and are not seen

The lost ones in the dark

The others do not hear them speak

Their loss they do not mark

The others think that all is fine

And none have gone astray

They speak with simple ignorance

“It’s such a lovely day.”

A tear traced down my cheek. “Yes,” I said, “that’s a start.”

I gazed at the girl, breathing slowly. I gripped the bow in my hand, a little more properly than before. Long moments passed. I listened to my heartbeat, and the infinite wind.

I looked down at my cello, my precious cello, and I wondered…

I wondered if…

…if perhaps I could set the other girl’s words…

…to music.

It was an honor and a pleasure reading this in the leadup to PVCF, glad to see it here!

11759401

Thank you for your editing work.

I know I said this before in private, but I think it bears repeating.

They say to write what you know, and your experiences in life and etched into every word of this story. It's clear that you've gone through *so* much in your time, so much pain. It's never easy to bare one's soul like this, and I think it's a testament to your strength that not only are you still standing, but you're able in some small way to share a piece of your story with the world. Thank you, for being willing to put yourself through the past again to share yourself with all us.

Stay safe, love, and I hope you can find the happiness that you so rightly deserve.

11762617

*hugs* Thank you

It's pretty much perfect for what it's saying.

There's something dark to considering, what if these characters were born in the human world? Would they be miserable? Never achieve their dreams?

There's a positive flipside to that, though, you know. People often look at characters in fiction, especially stuff like MLP, and think, 'I wish I could be that person.'

Maybe you are, but you've just been handed a much more difficult burden. Don't judge yourself as lesser.

11787222

Good point. Thank you.