The Mystery of Mysteries, part 2: Famous fictional detectives · 9:09pm Apr 25th, 2016

(This continues from The Mystery of Mysteries, part 1: Core narratives of genres.)

Famous Fictional Mysteries

The earliest mysteries (ignoring some stories by Voltaire) are usually said to be Edgar Allen Poe’s stories starring his detective Auguste Dupin: “Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841), “The Mystery of Marie Roget” (1842), and “The Purloined Letter” (1844). (Although the word “detective” didn’t yet exist.) Dupin has super-human powers of observation, concentration, and analysis, but explains his deductions as being simple and obvious. This is from the first scene written of Dupin (I have edited some of it out):

We were strolling one night down a long dirty street in the vicinity of the Palais Royal. Being both, apparently, occupied with thought, neither of us had spoken a syllable for fifteen minutes at least. All at once Dupin broke forth with these words:

"He is a very little fellow, that's true, and would do better for the Theatre des Varieties."

"There can be no doubt of that," I replied unwittingly, absorbed in reflection. In an instant I recollected myself. "Tell me, for Heaven's sake," I exclaimed, "the method—if method there is—by which you have fathomed my soul in this matter."

"I will explain," he said. “The larger links of the chain run thus—Chantilly, Orion, Dr. Nichols, Epicurus, Stereotomy, the street stones, the fruiterer. After leaving the Rue C ——, a fruiterer, with a large basket upon his head, brushing quickly past us, thrust you upon a pile of paving stones collected at a spot where the causeway is undergoing repair. You slipped upon one of the loose fragments, slightly strained your ankle, muttered a few words, turned to look at the pile, and then proceeded in silence…. You kept your eyes upon the ground—glancing, with a petulant expression, at the holes and ruts in the pavement, (so that I saw you were still thinking of the stones,) until we reached the little alley called Lamartine, which has been paved with overlapping and riveted blocks. Here your countenance brightened up, and, perceiving your lips move, I could not doubt that you murmured the word 'stereotomy,' a term applied to this species of pavement. I knew that you could not say to yourself 'stereotomy' without being brought to think of atomies, and thus of the theories of Epicurus; and since, when we discussed this subject not long ago, I mentioned to you how singularly the vague guesses of that noble Greek had met with confirmation in the late nebular cosmogony, I felt that you could not avoid casting your eyes upward to the great nebula in Orion. You did look up; and I was now assured that I had correctly followed your steps. But in that bitter tirade upon Chantilly, which appeared in yesterday's 'Musae,' the satirist, making some disgraceful allusions to the cobbler's change of name upon assuming the buskin, quoted a Latin line about which we have often conversed. I mean the line

Perdidit antiquum litera sonum.

"I had told you that this was in reference to Orion, formerly written Urion. It was clear, therefore, that you would combine the two ideas of Orion and Chantilly. That you did combine them I saw by the character of the smile which passed over your lips. You thought of the poor cobbler's immolation. So far, you had been stooping in your gait; but now I saw you draw yourself up to your full height. I was then sure that you reflected upon the diminutive figure of Chantilly. At this point I interrupted your meditations to remark that as, in fact, he was a very little fellow—that Chantilly—he would do better at the Theatre des Varietes."

Poe was capable of great feats of logic himself. In his article “The Philosophy of Composition”, which I highly recommend, Poe describes the astonishingly logical process by which he wrote “The Raven”, emphasizing that there was no “inspiration” involved, only intelligence, knowledge, and logic. So he knew that logic doesn’t work this way, and could have constructed a feasible feat of logic if he had wanted to. Instead of logical, Dupin’s ability is magical. We’ll see this again and again in other detectives.

Dupin has an odd detachment from humanity which manifests in his voluntary seclusion, his preference for leaving his home only at night, his lack of interest in being recognized for his accomplishments, and his boasting that “most men, in respect to himself, wore windows in their bosoms.” He disquiets his unnamed Watson, who describes Dupin as having a "diseased intelligence", by responding to the gruesome murder of a mother and daughter by saying, “An inquiry will afford us amusement.” He is active, bold, and delights in laughing at the police and in concealing how far he has gotten in order to make a sudden dramatic revelation. In short, he is the model for Sherlock Holmes. Jean-Claude Milner claimed that Dupin is the brother of the genius villain D___ in “The Purloined Letter”.

Sherlock Holmes appeared in stories written from 1887-1927, and is based on Dupin, as evidenced by many similarities between them, and by Conan Doyle's citing Poe's stories as a model. In the first Holmes story, Holmes resented being compared to Dupin and immediately claimed differences between them which did not, in fact, exist, and in “The Cardboard Box”, after Watson remarks on the implausibility of the scene with Dupin quoted above, Holmes replicates Dupin’s feat for Watson.

Holmes is super-humanly observant and intelligent, arrogant, detached from humanity, never visibly emotional, and seemingly unwilling or unable to fall in love. He has no respect for conventional thought or morals, and sometimes lets criminals escape when he judges their crimes justifiable. Between cases he often descends into depression and drug abuse. His lifetime adversary, Professor Moriarty, is a sort of evil Holmes.

Holmes is misogynistic, and not by accident on the author’s part. From The Sign of the Four, chapter 9:

"I would not tell them too much," said Holmes. "Women are never to be entirely trusted—not the best of them."

I did not pause to argue over this atrocious sentiment.

Holmes stories have a moral stance that Dupin stories did not, frequently showing crime as a result of moral weakness.

G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown (1910-1936) is a humble, unimpressive priest who solves mysteries. In many stories, some other characters laughs at the little priest’s plain appearance, jokes about the priest’s presumed simplicity and superstition, concludes the mystery has a supernatural explanation, and is then humiliated when the priest reveals a natural explanation. Unlike Holmes, who uses reason guided solely by empirical observation, Father Brown uses reason guided by observation but also by intuition, a reflection of medieval scholasticism.

Agatha Christie’s Hercules Poirot (1920-1975) is a physically unimpressive old Belgian exile in England, introduced as “a small man muffled up to the ears of whom nothing was visible but a pink-tipped nose and the two points of an upward-curled moustache.” He speaks apologetically yet impudently, is neurotically fastidious about his appearance and the shine on his shoes, and tries to always keep a bank balance of 444 pounds, 4 shillings, and 4 pence. One of his techniques is to make people dislike and underestimate him:

It is true that I can speak the exact, the idiomatic English. But, my friend, to speak the broken English is an enormous asset. It leads people to despise you. They say – a foreigner – he can't even speak English properly.... Also I boast! An Englishman he says often, "A fellow who thinks as much of himself as that cannot be worth much." … And so, you see, I put people off their guard.

He sometimes lets criminals escape, or to be punished extra-judicially. In 1960, Christie, probably a little tired of him, called him a "detestable, bombastic, tiresome, ego-centric little creep". I haven’t read these stories.

Sam Spade, the semi-hero of The Maltese Falcon (1929 novel, 1941 film), was the original hard-boiled noir detective. It is to the usual detective story as a story in which the hero fails to change is to stories in which the hero changes. This is symbolized by the fact that, though Spade unravels the murders that happen, he never solves the original mystery—he never finds the real falcon.

Wikipedia says, “Sam Spade combined several features of previous detectives, most notably his cold detachment, keen eye for detail, and unflinching determination to achieve his own justice.” Sam gives his view of the world towards the end of the novel:

“Now on the other side we've got what? All we've got is the fact that maybe you love me and maybe I love you."

"You know," she whispered, "whether you do or not."

"I don't. It's easy enough to be nuts about you." He looked hungrily from her hair to her feet and up to her eyes again. "But I don't know what that amounts to. Does anybody ever? But suppose I do? What of it? Maybe next month I won't. I've been through it before--when it lasted that long. Then what? Then I'll think I played the sap. And if I did it and got sent over then I'd be sure I was the sap. Well, if I send you over I'll be sorry as hell--I'll have some rotten nights--but that'll pass."

Sam does not love her, and she doesn’t love him, not in any sense that wouldn’t degrade the word. But his debate with himself shows that he thinks maybe he does love her, because what he feels for her is the closest he can think of as to what “love” might mean.

The novel keeps going after it wraps up the mystery, and ends on a note of psychological horror: Sam tries to flirt with his secretary Effie, teasing her a little cruelly for her innocence, but she shrinks from him in revulsion at—what? What he did? What he is? Or that he can do such things and not be broken by them? Sam turns pale on seeing the distance between them, and turns instead to his dead partner’s wife, Iva. He doesn’t like her very much but has been banging her since before his partner’s death. He realizes, at that moment, that that’s all he’ll ever know of love.

The girl's brown eyes were peculiarly enlarged and there was a queer twist to her mouth. She stood beside him, staring down at him.

He raised his head, grinned, and said mockingly: "So much for your woman's intuition."

Her voice was queer as the expression on her face. "You did that, Sam, to her?"

He nodded. "Your Sam's a detective." He looked sharply at her. He put his arm around her waist, his hand on her hip. "She did kill Miles, angel," he said gently, "offhand, like that." He snapped the fingers of his other hand.

She escaped from his arm as if it had hurt her. "Don't, please, don't touch me," she said brokenly. "I know—I know you're right. You're right. But don't touch me now—not now."

Spade's face became pale as his collar.

The corridor-door's knob rattled. Effie Perine turned quickly and went into the outer office, shutting time door behind her. When she came in again she shut it behind her.

She said in a small flat voice: "Iva is here."

Spade, looking down at his desk, nodded almost imperceptibly. "Yes," he said, and shivered. "Well, send her in."THE END

If the story is about finding the Maltese Falcon, why does it end with that scene?

Philip Marlowe is Raymond Chandler’s hard-boiled detective, who appeared first in The Big Sleep (1939). He’s outwardly similar to Sam Spade, but rather than being corrupt himself, he’s incorruptible. Chandler described his philosophy in creating Marlowe in “The Simple Art of Murder” (The Atlantic Monthly, Nov. 1945):

Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective in this kind of story must be such a man. He is the hero, he is everything. He must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor -- by instinct, by inevitability, without thought of it, and certainly without saying it. He must be the best man in his world and a good enough man for any world.

Marlowe is a different kind of loner. He’s the one virtuous man surrounded by filth. Chandler’s black-and-white puritanism made Marlowe repulsive to me—he hates gays, gamblers, drug users, rich people, and women, in a world in which the first four are always moral degenerates, and all beautiful women throw themselves at him, usually literally, begging for dirty, vulgar sex, and he slaps them aside, sometimes literally, in contempt.

I pushed her to one side and put the key in the door and opened it and pushed her in through it. I shut the door again and stood there sniffing. The place was horrible by daylight. The Chinese junk on the walls, the rug, the fussy lamps, the teakwood stuff, the sticky riot of colors, the totem pole, the flagon of ether and laudanum--all this in the daytime had a stealthy nastiness, like a fag party.

The girl and I stood looking at each other…. The smile would wash off like water off sand and her pale skin had a harsh granular texture under the stunned and stupid blankness of her eyes. A whitish tongue licked at the corners of her mouth. A pretty, spoiled and not very bright little girl who had gone very, very wrong, and nobody was doing anything about it. To hell with the rich. They made me sick.— The Big Sleep, chapter 12

I took plenty of the punch. It was meant to be a hard one, but a pansy [gay] has no iron in his bones, whatever he looks like.

— The Big Sleep, chapter 17

The bed was down. Something in it giggled…. Carmen Sternwood on her back, in my bed, giggling at me…. Her slate eyes peered at me and had the effect, as usual, of peering from behind a barrel. She smiled. Her small sharp teeth glinted.

"Cute, aren't I?" she said.

I said harshly: "Cute as a Filipino on Saturday night."

I went over to a floor lamp and pulled the switch, went back to put off the ceiling light, and went across the room again to the chessboard on a card table under the lamp. There was a problem laid out on the board, a six-mover. I couldn't solve it, like a lot of my problems. I reached down and moved a knight, then pulled my hat and coat off and threw them somewhere. All this time the soft giggling went on from the bed, that sound that made me think of rats behind a wainscoting in an old house.

...

"You're cute." She rolled her head a little, kittenishly. Then she took her left hand from under her head and took hold of the covers, paused dramatically, and swept them aside. She was undressed all right. She lay there on the bed in the lamplight, as naked and glistening as a pearl. The Sternwood girls were giving me both barrels that night.

…

I looked down at the chessboard. The move with the knight was wrong. I put it back where I had moved it from. Knights had no meaning in this game. It wasn't a game for knights.

I looked at her again. She lay still now, her face pale against the pillow, her eyes large and dark and empty as rain barrels in a drought…. There was a vague glimmer of doubt starting to get born in her somewhere. She didn't know about it yet. It's so hard for women--even nice women--to realize that their bodies are not irresistible.

...

I said carefully: "I'll give you three minutes to get dressed and out of here. If you're not out by then, I'll throw you out--by force. Just the way you are, naked. And I'll throw your clothes after you into the hall. Now--get started."

... She stood there for a moment and hissed at me, her face still like scraped bone, her eyes still empty and yet full of some jungle emotion. Then she walked quickly to the door and opened it and went out, without speaking, without looking back….

I walked to the windows and pulled the shades up and opened the windows wide. The night air came drifting in with a kind of stale sweetness that still remembered automobile exhausts and the streets of the city. I reached for my drink and drank it slowly…. I went back to the bed and looked down at it. The imprint of her head was still in the pillow, of her small corrupt body still on the sheets.

I put my empty glass down and tore the bed to pieces savagely.

It was raining again the next morning, a slanting gray rain like a swung curtain of crystal beads…. I went out to the kitchenette and drank two cups of black coffee. You can have a hangover from other things than alcohol. I had one from women. Women made me sick.— The Big Sleep, chapters 24-25

James Ellroy explained why Hammett was a better writer than Chandler like this:

Chandler wrote the man he wanted to be – gallant [and strong, and sexy] and with a lively satirist’s wit. Hammett wrote the man he feared he might be – tenuous and sceptical in all human dealings, corruptible and addicted to violent intrigue.

Marlowe doesn’t appear magical on the surface (except in his ability to be knocked out repeatedly without suffering permanent damage), but he is magically lucky. He’s another brilliant detective who does incredibly stupid things. He’s savvy and street-smart, yet like clockwork, he does the street-dumb thing: he finds murdered bodies or witnesses murders, and instead of informing the police, steals evidence from the scene and leaves his fingerprints behind; he hides murder case evidence from the police based on nothing but a hunch; he goes into potentially lethal encounters for clients he hates and refuses to charge them more than his expenses; he incriminates himself to protect people he doesn’t know from being suspected of crimes they might have committed… the list goes on and on. Every novel has scenes with him privately meditating on the unjustness of the world, yet Chandler’s world must have some pretty strict karmic laws for him to follow his moral code of hunches and poverty and always get away with it.

Isaac Asimov wrote a series of detective stories and novels (1953-1986) starring Elijah Bayley, a human, and R. Daneel Olivaw, a robot, in a world in which robots have no freedom or rights. The robopsychologist Susan Calvin, a human who identifies with robots, also appears in some stories. The plots usually turn on questions of how to interpret Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics, while their themes often deal with human prejudice against robots, and the philosophy of good and evil.

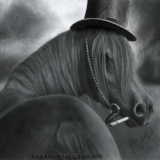

Dr. Who (1963-today) is called science fiction, but the plot is often a mystery: The Doctor appears someplace and sometime where things are not as they at first appear, and he must puzzle out what is happening, and prevent some bad thing from happening. The Doctor’s character is a warmer, fuzzier Sherlock Holmes, who travels with one or more semi-disposable Watsons and finds humans silly but endearing rather than tiresome. (That photo is of Tom Baker playing Dr. Who playing Sherlock Holmes.)

Dr. Who is presented as a genius, yet the Doctor is not rational. He never plans anything; he rushes into traps unarmed and trusts that he'll come up with something. He refuses to carry a weapon despite having run into hundreds of situations where a weapon would have been helpful. He solves problems with sudden inspiration or intuition rather than logic. He refuses to use consequentialist ethics; he won’t harm a Dalek or an insane Time Lord bent on destroying humanity. Again, he uses magic, or luck, not logic.

The Pink Panther’s Jacques Clouseau (1964-2009) is a bumbling idiot who solves cases mostly by accident. Yet he’s also dedicated, energetic, and creative (witness his elaborate training methods). Much of the humor comes from Clouseau misunderstanding everything that he sees and, far from being a detached observer, managing to remain all the time in his own fantasy world. He is magically lucky:

Including The Pink Panther here is like including Spaceballs in an analysis of high fantasy. I don't expect it to match thematically, since it's a parody, but it will share some attributes.

The Great Brain (1967-1976) is a series of children’s detectivish novels whose child protagonist, Tom Fitzgerald, alternates between solving crimes and committing them. He cheats his neighbors so often that the other kids eventually kidnap him and put him on trial in The Great Brain Reforms. His younger brother J.D. is his Watson. The stories often contrast Tom’s intelligence but lack of empathy with J.D.’s lesser intelligence but greater humanity, and show Tom mastering the world intellectually, but not really understanding how to relate to it. Tom is noteworthy for having a great but merely realistic intelligence, and for making money from his great brain.

Colin Dexter’s Inspector Morse (books 1975-1999, TV series 1987-2000) is a lonely, secretive, bachelor detective chief, at least in the one book I read (The Dead of Jericho). To quote Wikipedia, and I agree, “He claims that his approach to crime-solving is deductive, and one of his key tenets is that "there is a 50 per cent chance that the last person to see the victim alive was the murderer". In reality, it is the pathologists who deduce. Morse uses immense intuition and his fantastic memory to get to the killer.” Rather like Sherlock Holmes, he claims to use logic but actually uses intuition and magic.

After finishing The Dead of Jericho, I went back to check whether it was solvable. Technically, the reader had enough information to solve it before the reveal, but some of the crucial details appeared trivial in context, and I think it was not designed to be solvable, but for the reader to be able to recall all the necessary details after the reveal, and think it was solvable.

Tony Hillerman’s Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee (1970-2006) solve crimes on a Navajo reservation. I haven’t read any of them. I’ve read that they’re usually about conflicts between Indian and white culture, religion and materialism, and rich and poor. They’re written in third-person interior (basically first-person written in third-person grammar).

Stephanie Plum is the detective in Janet Evanovich’s novels (1995-present). I learned about her when I read Evanovich’s book on writing. I noticed that

- Janet Evanovich didn’t know anything useful about writing,

- half of the book was Evanovich reading scenes from her books, and

- all of the scenes she chose to read, in her book about writing, were dreck.

Stephanie Plum is an "unSue", who gets all the benefits of being a Mary Sue while being below average in looks and intelligence. She's pursued by all the hot sexy bad boys even though her most-described physical attribute is how overweight she is. They are okay with her banging all of them, though she can’t stand it if they “cheat” on her. It sounds from summaries I’ve read like the crimes are partly an excuse for Stephanie to have emotional drama and shift up her rotation of men. They're supposed to be romantic comedies, except the romance is unconnected to the comedy.

All characters in the scenes I've read act unlike humans, or animals, or even robots. Even when they're dead, they fail to act like dead people. Exhibit 1: Plum and her sidekick are trailing a truck on the highway, following a truck. A corpse suddenly falls off of the truck and manages (being an athletic yet insubstantial corpse) to hit their windshield, then bounce off, without damaging it.

Are they startled? Do they stop the car to find out who it is? Do they phone the police? No; they crack a joke, laugh, and keep driving. They aren't humans; they're Evanovichoids.

In the first novel, Plum doesn’t so much solve the crime as flail about stupidly and somehow not get herself killed until the crime solves itself. She "solves crimes" by incompetence, amazing luck, and being rescued by sexy men. For this, Evanovich gets called "one of the best and most inventive writers of “Strong Woman” mysteries." (By herself, apparently.) I do not have the patience to review these books further without exploding into a fireball of indignant rage at their commercial success.

Mma Precious Ramotswe is the detective in Alexander McCall Smith’s The No. 1 Ladies' Detective Agency (1998-2015). She’s a woman who was educated in Mochudi, the 10th largest city in Botswana, then moved to a very small village, where she decided to set up a detective agency (which is seen as a strange thing for a woman to do). She believes she values Botswana’s traditional ways more than the modern white ways, yet her independence, modern upbringing, and dislike of marriage bring her repeatedly into conflict with the village’s strongly patriarchal and family-oriented attitudes. She feels more than the usual amount of sympathy for the victims of wrong-doing, and this seems to be what drives her to solve a case once she has gotten into it. The novels are in third-person interior with head-hopping. If you’re gonna read just one detective novel, I’d suggest one of these.

Adrian Monk is the consulting detective in the TV series Monk (2002-2009), whose obsessive-compulsive behavior causes him to be unable to hold down a job or function in society, but also makes him aware of tiny details that help him solve cases. Much of the humor of the series is that crimes that are impossible for most people to solve are easy for Monk, yet everyday tasks that most people consider trivial are impossible for Monk.

House, a TV series from 2004 to 2012, stars Dr. House as a sociopathic but brilliant surgeon who is basically an even less-lovable Sherlock Holmes.

Dexter is the forensic expert / detective / serial killer star of eight novels (2004-2015) and a TV series (2006-2013). His father taught him to use his uncontrollable homicidal urges for good, by killing very bad people. He must solve crimes faster than the police to find enough bad people to kill.

There’s a mystery book club at my town’s library, which is composed entirely of retired women, who read nothing but mysteries about cooking, tea, sewing, and cats. It turns out each of these (cooking, tea, sewing, cats) is now a recognized sub-sub-genre of a huge new sub-genre of mysteries called “cozy mysteries”. Most mysteries published today may be cozy mysteries. They were apparently spawned by Murder, She Wrote. The sleuth is a woman who is not a detective but has a friend or husband who is, or is at least a cop. The town isn’t corrupt and the murders aren’t violent. She solves cases by talking to everyone in town, then putting together pieces of information.

I haven't read very many mysteries, so please add your own summaries of mystery series or detectives in the comments if you can, before we go to part 3 (Conclusions)!

A Mystery is About the Detective

Why was it so natural to organize famous mysteries by detective? Why do mysteries always have just one or two detectives? Why don’t we see great mysteries in which a team or a town cooperates to solve a mystery, like on CSI, or Scooby Doo?

If mysteries are whodunits, why are the detectives in great mysteries so eccentric and so finely-detailed?

Because the central narrative of the mystery isn’t about the mystery. It’s about the detective.

Let’s look at the commonalities among our detectives. I’ll enumerate my major summaries of the data with capital letters, and my main conclusions with numbers.

A. The most notable trait of a detective in a mystery is not intelligence. It’s that the detective is a misfit.

Usually either the detective laughs at or scorns the follies of the world (Dupin, Holmes, Spade, Marlowe, The Great Brain, Dr. Who, House), or the world laughs at the detective (Father Brown, Poirot, Clouseau, Ramotswe, Monk). The detective is superior to the others in the story (Dupin, Holmes, Father Brown, Marlowe, Great Brain, Dr. Who, House), even while the clients or criminals consider themselves superior to the detective (Holmes, Father Brown, Poirot, Marlowe, Columbo, Monk, Ramotswe).

The directionality of who laughs at whom might not matter. The point is that the detective is a stranger in a strange land who sees its inhabitants more clearly and objectively than they see themselves. Yet, despite this--or because of it--he can’t establish normal emotional connections with them. He is single, and has only one close friend, or none at all.

The detective often seems driven to action to delay some terrible ennui, or feels his isolation from society painful, and the reader is asked whether the detective’s uniqueness is a blessing or a curse (Holmes, Spade, Marlowe, Daneel Olivaw, The Great Brain, Monk, House).

Detectives are Misfits

Auguste Dupin: Exiled from the aristocracy, lives in seclusion, only comes out at night, sees humans as a source of amusement. Single.

Sherlock Holmes: Prefers anonymity, scorns emotions, emotionally crippled, dangerously depressed and bored with humanity. Single, misogynistic.

Father Brown: A deliberate misfit, he dismisses the world’s values and represents Catholic values in contrast to it. Single and celibate.

Hercules Poirot: An oddball foreigner who does not care whether people like him. Single.

Sam Spade: An almost nihilistic mercenary whose crucial strength turns out to be his cold, unemotional self-interest. Single.

Philip Marlowe: The one virtuous man in the valley of filth. The one man all women want, and the one man who won’t have any of them. Neurotically misogynistic.

R. Daneel Olivaw: Literally inhuman. Single. Also a misfit among robots, due to his android appearance.

Dr. Who: Literally an alien. Single, except for whatever he’s got going with River. I haven’t kept up.

Jacques Clouseau: Lives in his own fantasy world. Single.

The Great Brain: Verges on sociopathic; unable to make friends.

Inspector Morse: Single and unhappy about it, private, and sullen, but not neurotically so.

Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee: Living between and mediating between the Indian and the American, the religious and the secular, the rich and the poor. Joe: Married for one book, widowed for eleven. Jim: Single and dating for 11 books, married for one.

Mma Precious Ramotswe: A fiercely independent woman trying to do a “man’s job” and refusing (for several novels) marriage offers; a city person in a small African village; a traditionalist who isn’t traditional. Single; later marries.

Adrian Monk: Freakishly weird; unable to cope with even simple social interactions. Widowed.

Dr. House: A sociopath with a live-in prostitute.

Dexter: A homicidal psychopath. Single; dates. Should be faking his feelings, but the show never had the nerve to portray psychopathology honestly.

B. Detectives claim to use logic, but their deductions are more like magic or luck.

Magically logical, intuitive, or lucky detectives include Dupin, Holmes, Marlowe, Dr. Who, Clouseau, Morse, and Stephanie Plum.

C. The detective stands outside or above the law and conventional morality.

He may consider his own justice (Sherlock Holmes, Hercules Poirot, Dr. Who), or his tradition of justice (Father Brown, Philip Marlowe), superior to conventional morality or the law. He may solve crimes for entertainment or revenge that other people would solve out of moral outrage or patriotism (Dupin). He may be a part-time criminal, con-man, or otherwise sometimes commit crimes himself (Sam Spade, The Great Brain, House, Dexter). He may not be recognized as a person under the law (Daneel Olivaw). If there is a criminal mastermind, the detective will have more in common with that mastermind than with other people (Sherlock & Moriarty, Auguste Dupin & D___, Dr. Who and his two great enemies, The Master and Dr. Who).

D. A detective story is seldom written from the first-person or third-person interior point of view of the detective, and is often written from the first-person point of view of the detective’s companion. (Dupin, Holmes, The Great Brain, Nero Wolfe)

The Watson allows the detective to conceal his suspicions from the reader until it’s time for a dramatic revelation. GhostOfHeraclitus pointed out to me that he doesn’t only preserve the mystery; he also preserves the mystery of the detective’s character.

Tomorrow: The Sub-Genres of Mystery, and Conclusions!

P.S.-- Instead of complaining that I left out your favorite detective, write your own summary!

(looks around for the first person who will point out that the correct way to refer to "Dr. Who" is "The Doctor")

(finds nobody and decides not to)

Not to belittle your analysis, but I must say that mystery novel evolved a whole etiquette about presenting clues to the reader and remaining "solvable," with long lists of formal rules... It certainly tends to try to present itself as anything but a character-oriented story.

Does the character of a detective actually exist outside the act of solving a mystery, then? That is, would anyone ever want to see, say, Holmes trying to go through life without being engaged in a murder case? Could it be that we need to extend the definition of "character" here to present it correctly?

3895974

I know... but the famous mysteries don't do that. Don't you find that interesting?

Yes.

The first 7 story descriptions, in order. None are mysteries:

3896023

After Umineko, which is essentially a metafictional murder romance, and plays with formal rules incessantly, I can't help but wonder if those famous mysteries do use those rules, and just try not to advertise the fact.

Would they want to read them if they didn't know him for solving mysteries, though? Mentally replace all references to mysteries to something innocent but romantic in a randomly selected Sherlock fanfic, and change the names to A, B, C, etc. Would the stories carry any weight at all?

...actually, that sounds like an experiment where a single-blind test is possible.

3896072

I wonder if there isn't a real parallel there.

3896089

Depends on which pony we're talking about, but I suspect that audience preselection in this manner is a major factor in fanfiction in general. It remains to be determined just how major, though...

A fine summary of famous detectives, but you did neglect Dr. Spearman.

Woah, woah, woah.

No mention of Nero Wolfe, the detective books with a spin-off cookbook?

I feel like Arkady Renko and Nero Wolfe are being slighted here.

... listen, they can't all be text walls.

pondering the character "L" from Death Note, and he fits those traits pretty well. Though the interesting subversion is that this detective is not the main character. the story is mostly shown from the criminal's point of view. The readers already know who/why/how, so there's no need for the detective to magically pull revelations out of nowhere. In fact, the detective and criminal both know who each other are, and the real conflict comes from them logically maneuvering around each other to try to uncover a single scrap of evidence both ways.

Death Note is still a mystery story, but without any mystery for the readers to solve. or rather, it contains no logical puzzle or brainteaser for the audience, who are really paying attention for the characters and suspense. maybe this fits pretty well with your theory.

3896072

Prediction: Yes, but only if you replaced it with a similarly demanding and highly sought after accomplishment.

(say, oh I dunno, medical diagnosis)

I find it interesting that while you highlight Poirot, you left out Miss Marple. Was this intentional for some reason, and if not how do you think she fits into your observations about detectives?

3896252 3896280 There is one mention of Nero Wolfe, but I haven't read any Nero Wolfe stories. Want to add your own summary of him?

I grew up on PBS mysteries, Poirot being one of my favorites. I don't honestly know why. I was a kid, I didn't understand the stories in the least.

Of course, then I grew up and tried reading Sherlock Holmes, not to mention rewatching some of my old favorite shows, and I realized, not understanding them had nothing to do with being young, the way other movies and shows and books did. And while I've come to the conclusion, through other means, that I am not a "logical" thinker, seeing you describe not just Holmes as an investigator who uses "magic" to solve crimes explains a lot. This makes me feel A) that I don't need to count out mysteries as something I can't handle, and B) I probably needn't worry about trying to write them. This is a win-win, and I thank you.

On that note, though, no Lord Peter Wimsey? Tommy and Tuppence? You mention Murder, She Wrote but not its star? (Whose name I can never remember...) There's just so many, new and old! :V

I'd add another consideration to this Sherlock/Watson dynamic; powerful and sympathetic seem to work against each other somewhat in storytelling. By splitting the narrative with two characters, one can be the sympathetic/relatable one, while the other can be the interesting/powerful one. This eases up the burden on the storyteller, since they don't need to present all of these traits in one person.

Want to avoid Mary Sue? Use a sidekick lens.

Interesting analysis so far. I look forwards to part three.

3896405 Because I haven't read any Miss Marple stories. Would you consider writing a summary of Miss Marple?

I'm not trying to slight anybody. These are most of the mysteries I've read. I read a lot of Encyclopedia Brown and 2-Minute Mysteries when I was a kid, but that's all I can think of.

Oh, and those interested in Sherlock Holmes might find Doyle's story "How Watson Learned the Trick" interesting. Doyle clearly recognized the 'magic' he had based his character on.

3896434

Please feel free to add them yourself! I haven't read enough mysteries! I am unqualified to write this series of posts.

Her name's Angela Lansbury.

images5.fanpop.com/image/photos/28000000/Angela-Lansbury-angela-lansbury-28066666-454-594.jpg

Oh, wait, you're one a' them kids, aren't ya? Try this:

a1.files.biography.com/image/upload/c_fit,cs_srgb,dpr_1.0,q_80,w_620/MTE5NDg0MDU1MDMyOTIzNjYz.jpg

You remembered!

Though I should point out that there are at least two Sherlock Holmes stories narrated by the Great Detective himself (or at least I recollect two): The Lion's Mane (set after the retirement to keep bees on the Sussex Downs), and the adventure of the Blanched Soldier which is inexplicably narrated by Holmes. I have the facsimile edition of the Case-book of Sherlock Holmes here... somewhere, and I clearly remember that the story came with a little circular inset that boasted that this was the first Sherlock Holmes story narrated by him. It was clearly a Big Deal back in the day. Sort of a then-fandom's Episode #100.

And it was terrible. The whole concept of the stories was utterly ruined by this simple change. Holmes turned out to be, essentially boring. It's so bad that some people think a few Case-Book stories are actually forgeries.

I second the call for Nero Wolfe. He's an interesting take on the detective. In your typology, he's single, almost defiantly so, and has neurotic issues with women[1]. He also has several prominent misfit quirks: he grows orchids, he keeps to an exacting personal schedule, he's a gourmand and very fussy about food (he, famously, weighs 'a seventh of a ton'), he's incredibly lazy (he only really solves mysteries because he needs to pay his considerable bills) and if he could, he'd devote himself entirely to books, orchids, and fine food.

His most important quirk is that he absolutely will not leave his home. He's not agoraphobic. He's just lazy. He likes it in his brownstone. He manages to solve crime by having a Watson-figure: Archie Goodwin. Archie is his secretary and also his legs, eyes, and ears. Archie is the narrator and is equipped with, actually, a reasonably good brain (he's clearly a competent detective in his own right) and a very well developed sense of snark. Part of his semi-official duties is needling his boss into activity.

Nero Wolfe doesn't really solve crimes with much magic. It's mostly a sort of Poirot-ish approach of talking to everyone and teasing out secrets and such. Still, he's clearly a misfit and a lot of the fascination of the book series is the character of Nero.

[1] He doesn't seem to dislike them so much as he appears to dislike his reaction towards them? He mentions acquiring his considerable girth as 'insulation' against passions.

3896548

Actually, it's funny you said that. The character's name is Jessica Fletcher, but I always thought of her as Angela Lansbury because I was bad at differentiating actors and characters as a kid. :V

I'm really into an extremely narrow subgenre of mystery: the romantic mystery

In which one or more main characters in a romantic pairing have secret identities!

And one might be in love with the other's alter ego but not with their real identity, or maybe they love their real identity but not their alter ego!

There are so many unique and interesting scenarios that can play out in a story like that!

Hmm. Question. We're explicitly not limiting ourselves to literary detectives here, because Doctor Who and Monk are on this list.

Because if that's the case, I think we're missing a modern genre of detective fiction that seems to break the mold here. And that's the modern (and more specifically American) criminal procedural.

That's Law and Order and its various spinoffs. All the CSI's. The NCIS's. White Collar fits in here to an extent. Bones is... borderline. But we're talking a ton of shows with wide viewership that make a lot of money.

That genre eschews the single eccentric genius in favor of teams of detectives or investigators. And it completely shatters all of points A through D despite being, obviously and vividly, detective fiction. Some of the most successful and engaging detective fiction ever made, in fact.

This just isn't true unless we really stretch the definition of misfit to the breaking point. The people on these detective teams are usually relentless normal, with the sort of eccentricities that do not prohibit them from functioning in mainstream society. Lenny Briscoe is almost the ur-New Yorker. Gil Grissom is... odd, as is Sara Sidle, but they're within tolerances. So is Special Agent Jethro Gibbs and all of his team members; the most misfit member of that team is the girl in the lab who favors goth fashion, which is a purely aesthetic choice on her part that in no way impairs her functionality as either a forensic expert. Horatio Caine is fucked up inside but he's pretty normal as well. &c.

The closest to a genuine misfit is Temperance Brennan, and she's capable of holding down a high-stress, high-profile job and having romantic relationships.

Again, not the case in the criminal procedural. Those shows are all about grinding, about building a case by relentless chasing down leads in a logical and repeatable fashion that's wholly comprehensible to the readers and the people around them. The very first thing that happens on all those shows when the team sees a suspect they think looks a bit tasty? They pull their phone records, because duh. A Holmsian detective wouldn't need to do that; they'd deduce the last person the suspect spoke to on the phone using things like body language or how their contact list is arranged or some other nonsense.

Detective teams do not do that. In fact, the whole reason there's usually a team is because none of them are insane misfit polymaths; they're specialists with specialized talents who come together to form a deductive Voltron. Their leads come from DNA analysis, from finding a spent shell casing the criminal missed when they cleaned up the scene, from fingerprinting, from pouring over interrogation records until they notice an inconsistency.

They grind. They do not leap.

Almost always false. There are some criminal procedural shows where we're talking about a plucky band of vigilantes or mercenaries, but there's a reason this genre is often called the police procedural; the protagonists are nearly always cops. They're upholders of the law and conventional morality, and in the times when they're tempted to step outside of it the narrative almost always portrays that as, if not wrong, something the protagonists feel deep conflict about.

Not... really applicable here, we're talking about TV rather than books now, but like I said, Doctor Who and Monk are on the list, so that door has been open.

Isn't this interesting? In fact, it applies to a lot of the classic TV detective shows. Columbo. Perry Mason. Matlock. Murder She Wrote. Those shows didn't usually involve teams, that innovation wouldn't be pioneered in a big way until the 90s with Law and Order. So they're closer to the classical formulation, with a singular genius who often makes semi-magical leaps of deduction. But otherwise... protagonists who aren't misfits, occupying spaces that uphold the law and conventional morality.

You do of course have the detective shows that hew to the traditional formula more closely. Magnum, PI. springs to mind. But also interestingly, the only shows that tend to really embrace the old-school genre definition are TV adaptions of the literary canon.

Now, television is a different medium from written fiction, of course. The criminal procedural has a different operational space to play around in, and now that I think about it, mystery movies often hew close to the old-school genre definitions, don't they?

I'm not sure what conclusions to draw from this, but it definitely seems worth noting, because it's an enormous genre, not really a sub-genre, with significant divergent from the historical antecedents. And that seems to relate directly to the medium it takes place in.

3896072

Umineko goes beyond even that, in that the entire core of the story revolves around the mystery of the author*, and why they've written the stories they way they have. Beyond puzzle solving and straight into literary analysis if you ever want to truly understand the culprit.

*An in universe author, not the real world one. Although also kind of that.

Although when it comes down to it, Knox's Decalogue is more of a set of guidelines for good storytelling and to not screw over your reader with ass-pulls and deus ex machina.

3896523

I haven't read enough Miss Marple either, though I ought to fix that. I only asked because from the bit I recall, she seems to go against some of the tropes you laid out.

Another trope-breaker, who I could write about for you, is Nancy Drew. I read a ton of Nancy Drew as a kid. I might do that in a bit.

3896623 The police procedural is clearly a thing, and clearly a different thing, for all the reasons you list. Unfortunately all I've watched are the X-files and the first 2 seasons of The Wire.

I wonder if the main causal difference is that they're on TV, or that they're newer? Maybe the modern hero is a team player. Dragnet is pretty old, tho.

I'm interested in what they are & how they work, but I'm not going to worry too much about not including them, because I think they're not just a minor variation on the detective story. They're related--I think Columbo is an intermediate form; he's at least an oddball, like how he pretends to be stupid, and always has to wear his raincoat. And Cop-partner shows are midway between the lone detective and a team. But police procedurals are pretty different from detective stories, maybe more different than westerns are. Maybe more different than swords & sorcery is!

3896614 I have "romance mystery" on the list in part 3, but I didn't read any of those. I just meant mysteries that are also romances.

3896236 Oh my god I must read this.

aaand none of the copies on amazon ship to Canada. Great.

3896623

I think Gibbs clearly lands in Bad Horse's misfit category, not to mention Callen and Pride.

They are all part of a team so they don't have the true detective type methods either.

One thing they all do is that they all see themselves as standing above the law. They frequently bend the law and protocols to their favour and cover it up, not always successfully however.

3896724

I have one "detective" that I think could be worth including.

The ever smug Patrick Jane.

I think he uses mostly intuition to sole his mysteries, being a former psychic he reads people and tries to understand them rather than looking at evidence other than to spark new questions and insights, and from what I can tell he's open with what he does.

3896623

3896724

I wonder if some of the differences between the heroes of TV police procedurals vs detective novels stem from the differences between the two types of media. A TV show focused on a single very complicated character probably requires a good (read: expensive) actor for that role whereas a team of shallow archetypes is probably easier to cast. Furthermore, readers are stereotyped as being more introverted and probably would relate more to loner outcasts, whereas network television shows cater more toward an audience that might relate better to more socially well adjusted characters. Might be interesting to contrast the Holmes characters from the novels to the recent television versions of him to see if some of these hypotheses hold true (of course, many of the differences will probably be attributable mostly to the different eras in which the stories were produced).

3896724 Dragnet and the various CSI spins all seem to be more 'A Day In the Life' types of stories where the events being investigated frequently take a back seat to the interpersonal soap-opera relationships. To hit the real 'Detective' laying out the facts and motives of a case (or at least the TV type) you need to go back to Perry Mason. Admittedly black and white in more than just the film, Raymond Burr had a dead-perfect delivery and a way of peeling a suspect into a corner with their own words that made me never want to see the inside of a real courtroom.

3896724

Police procedurals like Law and Order and shows like CSI aren't even in the same genre, despite both being "crime dramas".

CSI is a detective show that uses a team of detectives instead of a single detective, but it more or less follows all the genre conventions - there's a misanthrope on the team, the show uses the crime being investigated as a means of characterizing the CSI team, and the CSI team doesn't fit in well (there are conflicts with the other CSI units in the city and other authority figures, and people often lie to or deceive the CSIs and force them to suss out the truth).

While they weren't as dysfunctional as many classic detectives, most of the team was defective in at least one way - one was cold and misanthropic, another had a gambling problem, ect. - and interpersonal and internal conflict is a big part of it.

By spreading out the dysfunction, they can make the characters more relatable as people while maintaining the drama from their dysfunction. They roll the Watson role into the team as well, and can always create new drama by bringing in a new dysfunctional team member to shake things up.

3896724

Columbo isn't part of the 'mystery' genre at all. From the beginning, the audience knows who did it and how. Columbo is more a drama focused on the interplay between Columbo and the murderer where the entertainment is in watching the latter sweat as Columbo gets closer and closer to solving the case.

3896697

I think Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys both break the model we've constructed, which is impressive given their prominence in the (older) American psyche. These detectives are loved by their family and friends; they are social butterflies rather than misfits (A). They do in fact collect clues (often with a group), and I seem to recall solving the book's mystery before the titular characters did from time to time (B). These characters do operate extrajudiciously, but they are often given permission from the mayor or their detective father, and they sometimes call in the police when it makes sense to (C).

Why are these teenage detectives so different from their adult counterparts? Could it be that children actually want to read about mysteries, not detectives?

3896623

3897084

3897146

It's always been my impression that CSI-and-co are really not mysteries. There's no mystery. No whodunnit. It was Some Guy/Gal and they'll find out which once they shine a green laser at something. They always struck me instead as being closest to a modern-day morality play. They present the world as a fallen place crawling with terrible people who would do you harm. Often the victims themselves are in some way ritually unclean (CSI is famous for doing fetish-of-the-week) and their death is nearly always related to this uncleanliness. Then our team of heroes shows up and restore the status quo ante and all's well in the world. The remained for the television hour is filled with standard dramaish soap opera stuff which serves in most television as all-purpose plot spackle.

A great example is the episode of CSI:Cyber I spent 6000 words eviscerating: throughout there's a powerful undercurrent of fear-peddling. The world at large mean you and yours harm, the farther something is from your day-to-day the more malevolent and incomprehensible it is and it will pounce on moral weakness instantly. Only an elite team stands in the way and they must be afforded all powers and abilities in order to keep the circle of safety that's your social bubble alive.

3897275

Well, I'm not sure about the Hardy boys, but Nancy Drew might be different in a way that illustrates Bad Horse's point. Keeping in mind that those books were targeted at young girls... Nancy was the kind of character young girls want to read about. In fact, thinking about it, she and her friends serve as kind of a condensed Mane Six; Bess was the girly girl, George was the tomboy, and Nancy was the kind of in between insert-y detective, a very Twilight kind of character (she had a car and a boyfriend and a rich, busy, widowed father, which is pretty much the same thing as magic when you're nine.) I totally admit I remember more about Nancy and her friends than any particular mystery.

As to the mysteries being solvable, that might be a matter of making sure kids get What it Says On The Tin. I can see kids being more likely to get angry if the clues to solve the mystery weren't there, just on principle.

3896396

Upon some further reflection... It seems to me that beyond the traits Bad Horse lists, the desire to solve mysteries is just as much an integral part of a detective character. The actual action of solving a mystery is not, but the desire is. Take that away, and we end up with just a misfit. If he doesn't have that potential to produce something spectacular, to apply his misfit-ness to the world, whether realized or not, (s)he loses a core character trait.

And that applies perfectly to Doctor House too. If he doesn't have a patient, he's just a jerk. :)

3897425

You could make the same character into a lawyer, a maverick astrophysicist, a sorcerer supreme etc. Just so long as the duel traits of overachieving asshole and intellectual superman are preserved (and I'd say the latter part is a purely aesthetic addition. In substance every gentleman thief, bandit prince and secret agent is a development of the same phenomenon- be awesome and you can get away with anything).

I'm honestly more inclined to believe mystery detectives are just rebranded superheroes now. The "add some memorable quirks and make them a member of a minority" formula seems to be at play here.

Also! Buddy cops- the missing link between this and the police procedural.

3897281

And traditional mystery novels aren't?

3897084 Was there a Dragnet reboot? The original radio Dragnet was entirely about solving the crime. It was too short for anything else--I bet an episode was 15 minutes. The cop narrating it had a flat-dead voice, like a robot, and it was inconceivable that he had personal relationships. That was in the late 1940s, long before Perry Mason.

3896697 I wouldn't worry about it. I think zero is "enough" Miss Marple, given how poor of a writer Agatha Christie was IMHO. Almost any contemporary writer is better. (I am basing this opinion on her short stories.)

3897281 3897205 3896283 Whether or not the audience knows whodunnit may be just one dimension of several important ones. From the discussion here, I'm beginning to think that there isn't so much a thing called a "genre" as a set of common elements with different affinities for each other. "Figure out what happened", "watch the misfit try to understand humans", "the lone wayfarer", "honest defenders of society fighting both the criminal and the bureaucracy above them", "violence", "moral decay of society", "romance", "the damsel in distress", "street smarts", "personal moral code", "revolutionary consciousness"--these are strips you can weave together in many combinations. There's a set that go together well, or at least frequently, to give us the closed-room mystery, and a set that give us the western, and adding one or two more strips to the weave could give you Swords & Sorcery or post-apocalypse fiction.

3897589

Not to the same extent, no. I mean it's hard to write a story which does not in some way feature morality, so I guess they are all morality plays, but the CSI subgenre seems by far the starkest about it. I mean, consider, say, The Adventure of Silver Blaze. There's a bad guy involved, I guess, but there's not that much of a morality aspect involved and that, mind, from Victorian literature with was normally drenched in moralizing and sentiment.

I guess the Philip Marlowe stories have a bit of a stark morality aspect to them, insofar as Marlowe is a sort of proto-Rorschach, but their ambiguity and darkness robs them of the pat nature that I see in CSI and a lot of forensic drama.

3897892

It'd be rather interesting to list them all, wouldn't it?

3897935

I have to wonder whether that's just a result of low production values though. How many episodes of CSI are there by now? I haven't watched any in years but I vaguely recall that the first one was more tactful than what the later series turned into. If you went through the bottom of the bin of true crime and penny dreadfuls you'd get the same sort of storylines I imagine.

Addendum: I went and skimmed through the first season CSI synopsis. There is an honest to goodness serial killer that leaves clues behind in every crime scene and Gil Grisham tracks him across the season. Honestly it seems like the series was conceptualized as "Detective Gil and Pals" until they realized the audience was only coming for the shock porn.

3897935

Oh, you nailed it! Have you read those stories?

(Of course you have. You've read everything. Or should I say.... uploaded to your data banks?)

3897281

But according to Bad Horse's theory of the genre, none of those really exclude it from being a mystery. Heck, CSI is hardly the first mystery thing to focus on the fetishistic or outsider parts of society; I have a mystery novel from the 1990s, The Bone Polisher, about a serial killer in the gay community. Though the book is actually fairly friendly towards the gay community, and the protagonist is sympathetic towards gays, it does portray the gay community as being full of oddballs.

The movie Clue from the 1980s (the best movie based on a board game of all time) has a woman who has murdered several of her husbands, another woman who is a madam, and a psychiatrist who had sex with one of his patients as main characters/suspects. One of the characters is also a gay man from the 1950s (who is, of course, the most straight-laced character in the movie), and there is a gloriously terrible French maid.

Really, mystery stories often focus not only on whodunit, but why they did it, and whether or not something else is going on (and also, on stopping the bad guy from doing bad things again). The aforementioned Bone Polisher makes it obvious pretty early on who the bad guy is, but who they really are, what their motive was in killing the particular person that they killed, and whether or not someone else is involved is much more ambiguous.

I'm so glad you included Mma Ramotswe, who is by far and away my favourite detective, and I'm also glad for your recommendation of that series.

I think Mma Ramotswe is a perfect example of a mystery that's about the detective, not the mystery, to the point where I think it would be fair to argue that they're not traditional mystery stories at all. (But they're still mysteries, right? Because she solves mysteries in them... wait the whole point of this is to try to define the mystery genre )

)

Anyway, would anyone want to read a story about her without the mysteries? The answer is yes, and in my opinion this is obvious because the mysteries aren't inherently thrilling enough to keep you reading.

Still, that interest in Mma Ramotswe doesn't really stem from points A-D. I can accept your description of her as a misfit - she seems strange in contrast to the society around her, a society many Westerners are not very familiar with, even though she's actually far more 'normal' than anyone else as far as Westerners are concerned. But you yourself don't include her in summaries B-D, and though I wondered that this might be because you hadn't read many of the books, I think it's also because she doesn't fit them. Okay, her assistant detective ("Associate detective!") Mma Makutski sometimes acts as "The Watson [that] allows the detective to conceal his [her] suspicions from the reader until it’s time for a dramatic revelation" but not that often.

Perhaps the lack of commonality explains why I read the No 1 Ladies Detective Agency but very few actual mystery novels.

IIRC she doesn't live in a tiny village, either. She lives in Gaborone, which is the capital of Botswana and its largest city by far.

3897892

I agree that genre is more of a statistical grouping. Bookplayer's description of fantasy novels as being "novels that people who like Fantasy would like" is probably pretty apt. As such, you get things which fit fairly squarely in the middle, and then outliers which are still unmistakably associated with the genre, and you might have things which ostensibly don't fit into the genre but somehow seem to do so anyway. It may also explain why the trappings of some genres get appropriated for stories of other genres.

3898028 Glad to find a fellow fan! The books and the TV show have merged in my mind. The TV show, at least the first season, was filmed in a village. The book indeed says Gaborone, but here is the description on the first page of the first book:

It gave me the impression of a small town.

3898035

What's the difference between a trapping, and a "real" element? Do trappings become real once you have enough of them?

3898061 I thought it was the other way around. Guess we'll find out when we get round to re-reading! Fair point about the TV show and the small village though. I'd like to rewatch it, but I don't think it's available on streaming platforms.

3897425 I wonder if Nero Wolfe really fits that role. He doesn't *want* to solve mysteries, he does so because he finds it the easiest way to pay the bills. I confess, I found him intriguing for that reason. Rather than having that drive to solve puzzles, he's content with good food and his orchids. It's his Watson that often is responsible for making him solve mysteries, unlike Holmes who would take on any case as long as it would occupy him sufficiently.

I wonder what a review of detective motivations would be like. I imagine it would fall along a spectrum of those who seek out mysteries to solve and those who are dragged or coerced into them. I wonder if you could find any interesting stats about them. Perhaps those who are dragged into mysteries aren't as prone to misfit status as others. Though as always, how you define each factor it is everything.

I have to nod to Trixie Belden books for being a big staple of my childhood too. she was a Nancy Drew type character, but for whatever reason, appealed to me more than Nancy ever did.

If you're listing Dr. Who from a Sci Fi (really fantasy) series as a detective, what about Harry Dresden from the Dresden Files? I feel like he was written to be like Philip Marlowe, but made to be less insufferable by feeling like he's Sam Spade on the inside. (Harry's always right and honorable, but thinks he's morally weak and corrupt.)