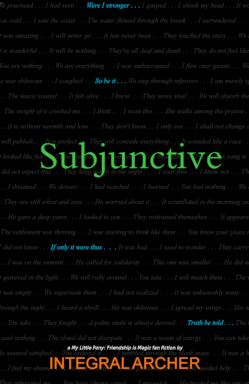

Chapter XIII: Imperfect

Hubris! That pernicious but inevitable corollary of the insolent audacity and abject complacency that are peculiar to any society to which, having never encountered resistance in the past, it must inevitably succumb at some point in its history!

I spoke as though we would reign untouched on this planet forever. So as I spoke, so the orators and writers of omnipotent nations had spoken, just as complacent as I, about the immutable potency of their land, their culture, their society, and their citizens. But, as is the course of nature, so too must that society face hardship—a hardship that will break them asunder, or at least fragment them such that the resultant scar is forever etched into the face of every citizen of that once proud and superior race, now thrown to the earth.

Perfect: in that moment, that word coursed through our heads with its mocking laughter, staying long enough to let itself be known, before evaporating and leaving us with its opposite.

But what word was left in its place? What word was there describing that opposite? There must have been one, but I couldn’t recall it! No matter how I tried, any possible word was forced away, and the pain came back.

One moment, I saw my brothers and my sisters victorious, successful. Cheers, exultations, successes, raptures, pride—and then . . . light, panic, screams; force, a power against which even thoughts, much less physical resistance, were permitted no existence; then crashes, dust, pain.

If you changed the order of the aforementioned nouns, it would’ve all been the same to me. They did not exist in my head thus; rather, they piled one on top of the other, strung together without meaning. Such was the power of the unnameable force that swept me away with as much effort as a routine exhalation, as if I were no more than a flea who had mistakenly and merely annoyingly found its way into its nostril: the order of my words, which had been so well-organized in my head a moment before, had been reduced to rubble and came to my mouth out of order.

Nonsense! Could anything more terrible have occupied one’s mind?

My only certainty was the last concept I mentioned, which now overwhelmed me completely. I knew for certain that only pain followed everything. All previous nouns collapsed to augment this last one.

*

I awoke once or twice at time intervals of which I knew not the extent, but my heavy head weighed my neck down. I collapsed, and a cloud of dust swirled up from the floor where my cheek had landed.

At length, I began to become aware of my own body.

In my right wing, it felt as though there were something resting uncomfortably on it. As time passed, it became less like an uncomfortable poke and more like a firm, stringent, tearing pull.

In my right foreleg, it started as a dull throb—as time passed, it went from the feeling of a snug embrace to a suffocating strangulation.

It was my fear of these feelings growing noisier that I managed to fall into a stupor much like a sleep, where only confusion, with its overwhelming paralysis, kept me from stirring. Confusion, along with a single word, spoken with a specific intonation:

Why?

*

I woke up.

Before anything else, a dry wheeze came from my mouth, leaving behind a burning imperative. The most turbid of rain puddles, one that had been defiled by the successions of passersby, I would’ve accepted at that moment. As I regained consciousness, a few more thoughts came to me, but they all fell back to this one and seemed in some way connected to this single concept: Water! Anything just to get some water!

I tried to stir. First, the left side of my body. That’s good, I thought; that worked as before—and I found the right side of my body myself pinned doubly: by my wing and by my right foreleg. I couldn’t see the impediments, but when I tried to struggle a pain came, gradually, in direct proportion as my exertions increased. When I stopped my struggles, the pain ebbed, retreating again to its strange seclusion, and there it lingered in the cells of my muscles, not gone but merely dormant, only waiting for just a little bit of energy in order to retaliate once again.

I coughed, my throat burning more fervidly than the rest of me. I swallowed my saliva in a desperate effort to mollify my thirst.

Why couldn’t I see? Why was there no light? Had I been buried alive, and was the debris packed around me so tightly that I couldn’t see the sun? A cool, fresh breeze on my face told me otherwise, but a dry breeze; I could feel no water in it when I stuck out my tongue.

Was it nighttime already? For how long had I been passing in and out of consciousness? And how long had I been lying there with these heavy objects on me? And why didn’t they hurt while I lay thus? If I moved—the most I could feel was a strange sensation through my spine. It was as if my nerves shouted not in pain but in warning, a threat even.

I couldn’t even move my torso, my wing and leg were pinned so close to their joints. Even when I lit my horn and tried to assault the problem doubly, from a mystical aspect as well as from a physical one, I still had not the power to move anything.

If I couldn’t get this piece of debris off of me, I’d lose my wing and leg!

I shrilled hoarsely, almost audibly on the hearing level of most creatures, the last of the moisture in my mouth evaporating, such that I could barely articulate the words intelligibly: “Help, my brothers and sisters! I’ve been incapacitated! Help!”

I let my head fall to the floor. I wanted to shrill again, but I had no moisture left in my mouth to form the clicks.

And then my ears perked up. What had I heard?

But that was the crux: I heard nothing.

That shrilling sound, thousands of voices vying for each other’s attentions and affections, a constant throughout my life, was now gone. In its place was a horrid ringing, a whine that droned its monotone into my brain.

(I would learn later that this sound composed the entity which was called silence, a word I had always known, but which had always been just an abstraction, as infirm a notion to me as the notion of the expanse overhead which changed to show blue dominated by a single point of fire or to show black and scores of twinkling sparks to the first sentient creature, to which he immediately gave the name firmament, not understanding it but calling it thus nonetheless, just to give a word to that direction of his countless vague gestures.)

Then, a few muffled voices displaced that whine. Footsteps outside!

“I’m in here! Come to me!” I shrilled again, finding the effort from my last excitement to speak one last time.

There was no response.

If it was one of my siblings outside, he certainly heard me, and he no doubt would have responded. But I heard nothing, save for the footsteps, growing even more regular, closer . . . and heavier.

I gasped as I heard the deep voices. Ponies! If they found me, I’d . . . what could I do?

Disguise immediately! I thought. None of them saw you; none of them would recognize you—change! Change! Change!

I assumed my old pegasus form as a tall figure kicked its way through the debris in front of me. The wan light from the street filtered through the dust and traced out in the air a tall, firm, erect shade. Its countenance was invisible, as deep and dark as the shadow that drew the entire form, but its silhouette, posture, and glare made the creature immediately recognizable.

“Foil!”

He leaped through the air, closing the distance between me and him in a single gallop, and emerged into the moonlight. I indeed knew him as the sentry I’d lectured to for those countless hours; yet something ineffable marked his glance and his stare. Fatigue was certainly there, as when last I’d seen him; but, somehow, as he stood there beneath that pale light, those features had become harder.

“How . . .” he began, staring down at me. There was no surprise in his voice, no shock, no terror. In my state, I couldn’t tell exactly what meaning gave substance to his tone—but it sounded vaguely like censure.

“How did this happen?” he said, his voice flat.

“I . . .” I stammered, searching frantically for the words to a lesson that I, in my panicked and bemused state, hadn’t prepared in advance. “I was hiding from those . . . creatures, the creatures, the black ones. . . . They were everywhere! And . . . and then there was an inundation of some kind—how else could I, you, we all describe it?—and then falling debris . . . and I’m stuck! And I’m thirsty, oh so thirsty . . .”

He nodded, as he usually did when he understood something; but, not as usual, his brow stayed furrowed.

“And why are you still in the city?” he asked.

“I need some water . . .” I groaned.

There was a pause wherein he stared at me, waiting for me to continue, unmoved by my plea for help.

“I’m stuck . . .”

“I can see that,” he deadpanned. “But you still haven’t answered my question.”

“I’m stuck,” I wheezed, “and I’m your friend. Your friend is stuck. And thirsty!”

Deep shouts echoed through the streets outside. I perked my ears up and tried to get his attention with a gesture of my head in its direction to those sounds which seemed so imminent and foreboding. But he didn’t move. He instead fixed me with that peculiar regard of his, in which for the first time since I’d met him I saw a flicker of something ulterior, as though it were deliberately held back and always had been. What was that something? I couldn’t tell. But had he been a scholar, I would’ve said that I saw in him that spark weld only by those who think—judgment.

“Help me . . .” was my final plea, as I prostrated myself before him.

At my words, he assumed that familiar, naive glance of his, and he looked around, finally hearing the noise. He mumbled something under his breath and approached me.

He reached into a pocket on his armor and produced from it a canteen. “Here,” he said. “Lift your head up. Drink slowly.”

The muscles in my neck seized with pain as I looked up to him, but I was finally able to get my lips up to the spout. The water was warm, filthy, and in it I could distinctly taste whatever had been in the pony’s mouth beforehand. And in my head swarmed vague thoughts, summing together to express the rapturousness of that fluid of succor, from which relief, satisfaction, and pleasure tickled my throat with their introduction, promising an augmentation later in the line; and I looked upon the sentry, as he held the chalice to my mouth, as one looks upon a god.

And suddenly, he ripped it away, and I gave a cry like an infant mammal pulled from his mother’s teat.

“That’s enough,” he said. “I don’t want you throwing up on me. Now, let’s see here . . .”

He moved behind me, out of my line of sight, and I felt the weight on my body shifting. Suggestions of pain made themselves known in the clenching of my teeth, but I did not scream.

“This doesn’t look so heavy . . .” he mumbled.

A deafening crash cut my ears as the debris fell away—and then nothing! I couldn’t even feel my own presence! My lungs expanded against nothing as I breathed deeply once again. Where was my mass? Surely it would take more effort to stand up than . . .

Unthinkingly, I put my right forehoof gently on the ground, placing a small amount of weight on it—but I jerked up with my shoulder as a strange sensation ran through me. But it wasn’t pain. It was a silent cry. Still lying on the floor, I gently touched the estranged limb with my left forehoof. I could feel it; that was a good sign. But an instinctive, indescribable imperative warned me against putting any weight on it.

Before I could get to my feet, the sentry was in front of me and had picked up his spear. I hadn’t even seen him move.

Shakily, I rose. “You saved me . . .” I murmured, “and—”

“Do you think I’m stupid?”

“What?”

“I said”—he stepped closer to me, and my fur bristled—“do you think I’m stupid?”

I couldn’t speak.

“Do you think that I’m an incompetent?” he continued. “Do you think that I’m so thick that I can’t see through your pretenses?” he said through his teeth. The muscles in his neck pulsed.

In front of him, I couldn’t lie, not if I wanted to maintain my personal plausibility. So I said only the truth.

“I never said that.”

“You implied it. You implied it every one of our conversations. So you don’t think I’m smart, eh? You think I’m stupid? You think that I can’t see?”

He took a step closer. When I tried to look up into his eyes, I saw only his protruding chin hanging over my head. I couldn’t stop my spine from compressing with the weight he held above me.

“But you’re wrong,” he said. “Not wrong in what you say, of course. Because you’ve never been wrong in what you’ve said—only in how you’ve said it.”

He waited for me to respond, but I said nothing, for I knew that anything I could have said would have been a lie. And I couldn’t, not with him and his spear in front of me. The weapon’s fixed point shone brighter than the moonlight it reflected, and for a long while still it loomed, tenebrous and quivering from this angle, as though it were shuddering to hold back a force powerful enough to expose all obscurity.

The marching sound grew louder. The sentry positioned himself between me and the debris and swore under his breath.

The glare he shot me could have rivaled any I had ever seen from any of my brothers or sisters.

“What was the last thing you remember?” he asked.

“I . . . don’t know.” I swallowed. “And where . . . are they?”

He rolled his eyes. “Gone. Well, scattered. We’re still picking up a few of them here and there, but we never find them together. Only individually. And individually, they’re like flies.”

A sound came out of my mouth—a grating, caustic, horrible sound. I knew it was I who was making it, and I knew why I was making it; but I didn’t know what to call it. Was there a word to describe this sound composed of so many degrees of despair? A wail? No, it was subtler and more complex than that. And a wail is cathartic. This sound wasn’t cathartic; it hurt my chest just as much as it hurt my ears. But I couldn’t stop.

At length, the sentry spoke. “I’ve never heard you laugh before,” he said. “But now that I have, I wish I hadn’t.”

Oh . . . oh no. No, it couldn’t be. It couldn’t be because . . .

“I don’t believe it!” That was a wail.

“What don’t you believe?” the sentry said.

“What . . . where . . . how . . . why? . . .”

“They’re gone.”

“I don’t believe it. . . . I don’t . . . I don’t . . .”

“And why don’t you believe it?”

“I don’t believe it because . . .”

“Because you don’t want to believe it?”

Before I could answer, the sentry grabbed my mane in his mouth and dragged me through the debris. “Come on,” he said through his teeth, “we’ve wasted enough time as it is.”

I scratched helplessly at the ground. “Where are you taking me!” I screamed.

He said nothing but kept us on his unknown but inexorable march.

Cool air greeted my nostrils—only air, no light except from the occasional stray lamp and the moon from where I could catch glimpses of it. How was it already nighttime? Had I been incapacitated for so long of a time? How was this possible?

These questions, among many others, raced through my mind, a new one taking form with every step through the darkened city. He led, his teeth tight around my mane, and I tried at every moment to regain my balance and to keep pace with him. There was barely enough light to see by, and the sentry moved so fast that I was unable to focus on any one thing long enough to identify it. The city passed before me as a blur at an immutable pace. The moment I thought I knew where we were and where we were going, he would take an abrupt turn, and again the buildings in my mind would be razed. In that semidarkness, it seemed to me that this was the real city, now dead and dark, and that before, when I had first seen its ramparts, its sparkling turrets, and its dazzling roofs, it had only been a facade, to lure us in, to wait until we were weak when at last it would show its wretched, true self, as it appeared now. But the sentry moved without question, without thought, through the twists and turns of the streets, by the light of a moon which would now dim, now cast indirectly around us, or now blink out and leave us in complete darkness, but never showing us our way directly. The sentry kept me to him thus: through force, upon my mane; and through my fear, upon my inability to walk without him.

At length, he stopped, let go of me, and I felt the air cooling between us as he stepped back. No longer could I hear those confused, random voices of the city. Here, only the wind, intermingling with the sound of his heavy breathing, came from behind, as though the city, with its constant din, had blinked out, leaving behind a frigid void.

When I opened my eyes, there were no shapes in front of me. A faint white line traced the extremity of my vision, which I took to be the horizon, but I could see nothing breaking it apart, neither stars above, nor buildings below.

The sentry waited, as though expecting me to walk.

I could see nothing, not even the ground in front of me. I reached my right forehoof out, pushed it down gently, careful not to put any weight on it—but where it should have made purchase, I felt nothing.

I turned to the sentry. “Where are we?” I asked.

“The rim of Canterlot,” he said. “The end of the mountain. One more step, and it’s a straight fall to the earth.”

“Why are we here?”

“Because the patrol is looping back in a second, and if we were to continue on the street, we’d run into them, and then they’d make me do something I couldn’t let myself do.”

“What?”

“Arrest you.”

I blinked. “I . . . don’t understand.”

He laughed, not a friendly one, but a horrible, deriding sneer out of the depths of the darkness.

When he was done, he inhaled deeply, drowning out the sound of the wind, and stepped closer to me, not close enough that I could see his facial expressions, but close enough that I could see his eyes, which glowed from his place in the shadows.

“Martial law,” he said. “We have orders. We’ve established several exclusion zones in the city. Outside of these zones, no matter where you are, you are to obey us without question, and we may or may not take pity on you, according to our discretion and Their Majesties’. Inside of those zones, however, we are to arrest you without question, whether you are a pony or whatever; anything that can move, speak, walk, slide, or buzz is to be arrested in these zones. Until this matter is resolved, until we find every last one, nothing in Equestria, not even its citizens, has any rights.”

He paused. Then, he scowled, his voice slow and deep: “You stand now in my zone.”

I tried to speak. I mouthed the words: “So . . . you’re not arresting me?” but I could not hear them.

“No,” he replied. “I’m betraying the words of Their Majesties by not arresting you. But I can’t. I won’t.”

I could feel neither warmth, nor amicability, coming from him. From him emanated nothing but censure riding on impending vehemence.

“I don’t know . . . what to say,” I stammered, “or what to think. But . . . thank you. Thank you, my friend. I’m glad I’ve . . . earned your friendship and your . . . respect . . .”

He leaped toward me, and I tried to shrink back, but my foot slipped against the side of the mountain and dipped briefly into the abyss. Inches from me he stood, and the light from his eyes illuminated his cheeks, his furrowed brow, and the bared teeth between which hot, sticky, angry air lapped against my neck, causing me to sweat.

“Respect you?” he growled. “You think I’m letting you go because I respect you?” He laughed. The bottom of his throat was darker than the drop behind me.

“It’s precisely for the reason that I don’t respect you that I’m letting you go.”

I stood silent.

“Don’t understand?” he bellowed. “You say you’re a scientist—well, you have the evidence; now form your conclusion. Still quiet?” he said, after he got no response. “That’s right. I know you well enough to know that the facts you can take in, no problem—but conclusions and inferences . . . those are alien to you, aren’t they? Is that why you tried to befriend me? Because in me you could sense something in you that was lacking but which you needed? Ah, but you have me rambling now.”

The tip of his spear grazed the fleshy part of my neck. “Fine,” he said, “let’s do the speculation together. What if I were to obey orders? What if I were to play the good little grunt and arrest you as I should now? Let’s think: Since I found you, it would be I whom they’d make to take you to the dungeon. And that’s far; I’d probably fall asleep on the way. But supposing I were to get to the dungeon, they’d make me do the paperwork to sign you in. And how would I do that, especially on somepony like you? Name? Date of birth? Age? I know nothing. I suppose I could take yet more time to talk to you some more, make some more inferences about you—but, really, you’re only flimsy, disconnected ideas; there’s nothing in you concrete, and I would get nothing more than I have now. So then I’d have to go through their procedures in filling out the details I don’t know, more forms, more time. So, maybe, that’s three more hours. But that’s not enough: then, I would have to see you every day: First, they’d make me splint your wing and leg. Then, they’d make me feed you, would make me let you stretch your wings, and do all that garbage they call due process and rights of the accused. They’d make me talk to you, to bring you something when you needed it, to wait on you, to demean myself for your sake. Can you imagine my doing that? I, once a respectable soldier, upright and proud, now scrubbing the cell of this . . . what is this? What are you? Look at you, who had carried this image of superiority, haughtiness, and grandiloquence, who fancied yourself the mightiest image of everything that was lofty and proud and strong—now you’re abject, dirty, distressed, distraught, and still outside in the streets of the city! Can you imagine my dirtying this immaculate armor while scrubbing the walls of your prison cell? Oh, you would love that, wouldn’t you? To bring me down to your disgusting level—that would bring you no end of joy, wouldn’t it? Well, you, doctor, professor, teacher, worm—you don’t get that treatment. You’re not an armed robber who fights back when he encounters the authorities; you’re not a murderer who, when faced with the evidence, nods his agreement as his crimes and sentences for which are read. At least to the common thug, there’s a certain respect to be had when he stands up for his crimes and accept his punishments with a bowed, but upright, head. Not you, though. Here you are, not only trying to slip through the shadows, but failing, falling into the dirt, and needing help to recover yourself from your own incompetence! Such a creature isn’t worthy of due process, much less the help that he needs, which I rendered only because there’s a tumorous seed you planted in my brain, a seed whose stalk I hope to raze by doing this now and forgetting about you. Because you’re all alone now. You’re alone here, and we are your enemies. The longer you stay here, the harder we’ll press back at you. Have the courage to stay here, and maybe then that will earn you some respect, perhaps even a sufficient amount to allow me to throw you into the hole you so desire. Until then, no, you don’t deserve that. If I am to dirty this uniform, let the stain be from the dirt of this mountain and not from the odorous mud of the prison cell you wouldn’t deserve. Our next meeting, though—then you’ll see what happens when a soldier respects himself and his adversary enough to react.”

He spoke so sharply, so definitively, that I could not understand the words themselves or how they fit together. But the vague notion that they intimated was enough for the message to get through. To me, the language he was using was unintelligible, and I knew that that was only my fault.

He reared up and kicked me, square in the torso. All four of my hooves were in the air as I plummeted. As the air fell around me, I could feel my breath rising away with it.

*

It must be a dream, I thought, for I felt no sensation of falling through the air. The city was receding above me, forever scrambling to escape my sight the more I tried to look at it. It wasn’t until I heard the woosh of a lower peak barely missing me as it sliced the air by my ear that I realized it: I was falling from the mountain.

I had one good wing beneath me. It twitched in the breeze, as though preparing to flap of its own accord—but a frosty chill which passed through me at that instant folded it against me and kept my lame wing twirling like a stray maple seed above.

It would be easy, I thought: it would be easy to do nothing and to just crash upon the earth, whereupon these hardships, injuries, losses, all that had pulled at me for the past few hours with millennial potency, would just vanish. A small part of me screamed to stop, that if I fell now there would be so much that would not be done and that I would be leaving the world with missions failed, promises broken, and desires unfulfilled. Then the wind came back, silencing that panicked scream, imparting with cool words the notion that, when I left the world, none of that would matter.

It was a lucid dream: not in the sense where the dreamer recognizes his state as absurd, despite how real it appears to him, and takes advantage of his awareness to indulge his fantasies and lusts, but in a sense quite opposite, the state where I recognized what I was experiencing to be reality, yet it seemed unbelievable.

I could do nothing . . . just let myself be carried away—but no! My family needed me! But could I believe that we were gone, dispersed?

I couldn’t recall the image of a member of my family. When I tried, strange, confused thoughts came, and once or twice I thought that I could describe the forms . . . a small black horn . . . protruding canines . . . and wings, delicate transparent films that whistled as they twitched. And—oh yes!—this was not the only form. Hardly would these shapes come to me when they would be replaced with complete others, innumerable, varied forms, unrecognizable; and I knew I needed to find some way to put them together, for they were all the same thing, but . . .

. . . But what were they? Could I speak to that single identity? How could I, when such an incomplete, indescribable form existed in its place? And if I couldn’t speak to that identity, how could I be sure it had ever existed?

Was there anything that was constant? . . .

Yes . . . their tongue! It consisted of high-clicked shrills, similar to a bat’s, and they spoke in possibilities!

The subjunctive mood! From the moment I was brought into this world, I heard it; even if I couldn’t see them, I could hear them droning it into my ears!

And where was that droning now? Wounded! That soothing, warming constant, using its silence as its cry to me, its protector! To bring it back, to propagate it, to sustain, lift, hold it where it had once been—that was I!

*

I flapped my good wing as hard as I could. Though my downward velocity decreased considerably, it was at the expense of an extreme lateral spin, such that I almost blacked out. When I identified the problem, gritting my teeth, I feebly extended my bad wing, despite the pain, despite the water filling my eyes.

I felt the impact of my body upon solid matter, throwing up a whirling abyss around me and my confused vision. Though what I felt against me was definitely solid, my passage through it was followed by a sound much like the sound of water landing on a hard surface, and the mass bended to me and retarded my descent much as a fluid would.

Where the softness ended, sharpness began, slicing against my face, picking at my legs, digging its hardest into my back, and tearing away the last of my breath. The only thing I could do was wait until I stopped.

The biting slowed, piercing its last few attacks into my flesh, until, finally . . . I was no longer moving.

I blinked and rubbed my eyes with my good forehoof. With a hind leg, I gently tested the arms cradling me. My foot rebounded with a familiar sound.

Wood.

A large, irregular canopy stretched over me. A zephyr whistled past, and the canopy quivered tentatively. Two or three of the stars above me were obscured, replaced by others in different places. When the exhalation passed, when the canopy snapped back into position, the new stars departed, and the old ones returned, as if the shelter had just winked at me.

A tree bough.

There I sat, my breathing heavy. At length, a smile came to my face.

Here, in the cradle of nature, for the first time in a while, I felt relaxed. There were problems, I knew, but they didn’t seem to matter. I could sit here for a little while yet, and I wouldn’t be bothered by anyone.

My breathing slowed, and I closed my eyes, folding my forelegs over my chest.

What was it? Bliss? . . . no, perhaps too powerful of a word. Peace . . . yes, peace was the word that captured this feeling entirely.

Yes . . . peace. No other word to my knowledge carried the meaning that filled me at that moment—not even one that I could think of in my native language.

Peace.

*

My ears perked up when I noticed that my heart rate was beginning to increase. I started to breathe more heavily.

My anxiety begot more anxiety.

What was the problem? I had been so at ease a moment before, but now . . .

And then my wing pulled at me. At first, it nagged—but then it came with all its force, and I could feel the debris landing on it once again. I was about to wrap it around me and put it in my mouth for comfort when my leg started in the same wise.

I hadn’t cheated my injuries at all. They had always been there, held back by something, and now here they were. They had been waiting to strike when I least expected them, to hurt me when it would hurt the most—now, at this moment wherein I thought I was finally free.

My endorphin and adrenaline supply had just been exhausted.

A scream effused into the nighttime air from among the boughs of the Everfree Forest, sending several sleeping birds flying from their nests.

Ah, now this one, oh this one is something unique. You paint such a marvelous picture, simple, elegant, and starkly harsh.

Had to go over the prologue again to make any sense of this one. But I'm no longer confused!

Instead, the confusion has been replaced with lamentation at the sinking of that most pristine of vessels.

ErreFoil! Oh, sweet ErreFoil! What I wouldn't give to salvage you from the maelstrom to which you have succumbed!

Foil's monologue was great. I can only imagine the betrayal he feels, and the questions that must nip at his tail. Why didn't he see the truth sooner? Why did he fail in his duty? How could he have been so blind? And now a new question dogs him: did Errenax deserve to be cast from the mountain? Did he earn that right?

I always read this story aloud, and it flows beautifully.

Technically Errenax never told Foil he wasn't going to invade Canterlot and destroy everything they hold dear.

"I realized, the moment I fell from the mountain, that the city would not be destroyed as I had planned. It continued falling away into that starry expanse, of which I had only a fleeting glimpse. I have tried to speculate where I might land—I must admit, however, such conjecture is futile. Still, the question of what pony might one day discover my broken body is unsettling to me. I know my apprehensions might never be allayed, and so I close, realizing that perhaps the ending has not yet been written."

4577214 this is the best comment ever

Oh, stars, it's just so glorious that Foil's whole phillipic is one long string of subjunctive (about future conditionals). That says so much about how Errenax underestimated him, and that's such a linguistically perfect way of twisting the knife.

I feel as though something were missing between the last chapter and this, some temporal reorientation.

inb4 lost cities

8477721

its the prologue

7622138

wow, i didn't even notice that