Chapter XIX: Defective

All at once, the brakes on the train locked, and the screech of iron on iron rang through the car.

Instantly, my eyes were open. I grabbed a hold of my seat as I was thrown forward by an invisible force. Beside me, the pegasus too was trying to brace herself. Every figure in the train’s car was leaning forward in this awkward manner, impressed as we all were by this mysterious presence bearing down on us as forcibly as the question of its origin.

The force relented. I slouched in the same attitude as before but on the point of the sharpest edge and alert, my heart palpitating, my temples throbbing.

I leaned over to the pegasus. “What is happening?” I asked her.

“I don’t know.”

Voices commenced to redound in the car, carrying a motley assortment of words but which all directly or indirectly carried the same connotations of trepidation. But the most paralyzing thing was not the question; it was the knowledge that there was no immediately evident way to find the answer.

The pegasus touched me on the shoulder. “It’s alright,” she said. “I’m sure it’s nothing.”

In the entire car, she was the only one who was in the same attitude he was in before the train had convulsed without warning. At the moment of the lurch and subsequent screaming of brakes, everyone’s expression reflected his origin and nature, the transparency of which proportional to what he had to hide: the pegasus, who trusted and loved without question, was unmoved; the Canterlot commuters, who had clutched their luggage and shot each other wary glances throughout the course of the ride, now grew anxious; and I, for my part, could not breathe, so choked with fear as I was.

At length, a pony in a blue uniform entered through the door conjoining our car to the front one.

“Conductor,” said the passenger closest to the door, “what’s going on?”

The pony called the conductor put on a smile for the passenger’s sake, said something short and hurried, all the while gesticulating with a forehoof in a supplicating manner, then turned to face the rest of the car. But the look on the passenger’s face did not augur well for what the conductor was about to say.

“Fillies and gentlecolts,” he began. “Please remain in your seats! There is no cause for alarm. There is a slight delay, but we will be along shortly.”

“Why are we slowing?” another passenger asked.

“Nothing to worry about,” the conductor said. “We’re approaching the Canterlot Junction. The Royal Guard is stopping us for a routine inspection.”

This nonchalantly spoken comment set astir suppositions throughout the air of the car.

“You are in no danger!” insisted the conductor. “But if a soldier of Their Majesties’ legion should come into the car, you are advised to answer his questions and submit to any searches he requests.”

At this, interjections leaped from the passengers. The conductor grimaced before moving through the length of the car to the next one, as worried comments rained down on him from all sides. He could not make it to the end without splaying his ears and bowing his head.

And then, without transition, the gentle rolling grasslands and prairies blanked out, disappeared altogether, and were replaced with a void panorama, blacker than a starless night. At intervals, a sharp yellow light shot its way through the train’s window, vanishing as fast as it appeared, only to blink back in again, and its intensity shone through to me in the manner of an injunction, each iteration more forceful in its assertion.

“We’re in the tunnel now,” said the pegasus.

As the train progressed, the flashing slowed; until at last, the wide arc of light cut through the train one last time before settling itself across the interior of the car.

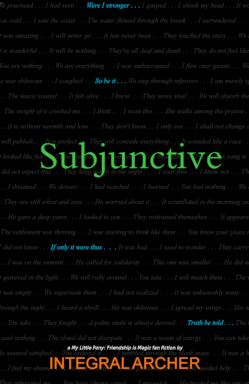

The train was still. Slowly, the anxious conversations crept up in tone. Suppositions bounced off the windows and into my ears. Suppositions which, in no small part, fed that ballooning and fearful subjunctive mood, feeding in its turn that curious indicative with its myriad questions:

Was it something to do with me, with us? Was this checkpoint my family’s fault? What did the Guard want? What were they looking for?

A far-off blur caught my attention. I peered down the aisle and looked through the windows of the multiple doors that separated our car from the preceding ones. In the distance, two cars down, gleaming metal plates stacked upon figures who looked as immovable as rocks were surrounding a pony whom they had ordered to stand and whose legs were visibly shaking as they stared at him.

One of the iron figures bent down to the smaller pony, and when the former tilted his head forward, the motion revealed his horn, which glowed as magic flared from its tip, expanded, and then slowly encircled the latter, whose teeth chattered as he was enveloped.

Then, as the magic reached its maximum, it pulsed its mystic presence through the air of the train, dispersing as it traveled, but its invisible form prodded against me. For a brief moment, I was exposed. In the span of that flash lasting no more than a millisecond, which only I’d felt but which had been there nonetheless, I sat there as the naked changeling, revealed to the ponies around me, my black skin contrasting to their varying colors.

The spell dispersed, but not the apprehension. Quickly, I grasped my face with a hoof: the long snout, the large nostrils, the blunt teeth. . . . I was still in my pony form.

The pony reappeared, distraught, but to all appearances unharmed; and the iron ponies moved away from him.

I watched as they repeated this process on another pony to the same effect. And this time, as the magic reached its climax, again the same feeling of panic, the same naked sensation, but magnified so intensely that it felt as though there were claws ripping at my affected skin and pulling at my ersatz hair. My whole being retched at my covering. My innards shifted as if my outer layer were aflame.

What are they doing? I thought, as the magic relented and the pony they were terrorizing sat back down. What is this magic which causes me to tremble? . . .

A soldier standing by turned and looked in my direction. I first saw his dark red mane contrasting against the brightness of his armor . . . but even brighter still were his eyes, glistening even at that distance with a perception and intelligence that struck through the length of the cars between us, toward me, seeing . . .

I quickly pulled my head out of the aisle, lest Foil see me.

It was he! That being whom I’d lectured to for countless hours back in Canterlot, whose assiduous mind effortlessly sharpened knowledge into a spear—it was he! It was undoubtedly the sentry Corporal Foil!

Had he seen me? I dared not to look back.

I then knew what that magic the unicorn with them was using; I’d known it from the first feeling: they were looking for a changeling. They were looking for me. Foil was looking for me. When he had had a right to my life, he had spared me when he would have spared no other, on the only condition that I stay away from him and Canterlot. And now here I was, underneath the mountain, his city right above me—I, who chose to tempt him once more . . . here he was to expose and take me!

Shakily, I rose to my feet. Immediately, the pegasus asked where I was going, and I managed to fob off her objections with some hastily made comments short enough to be made in a moment but verbose enough to not allow her to see that they were hollow.

I waited for an opening to move. At last, the pony in the seat in front of me stood up and moved into the aisle. It was then, when he obstructed the window, that I took the opportunity to move in the opposite direction, down the aisle, toward the front of the train, away from those rapidly approaching sentries, Foil at their sharp head.

The steps clattered under my weight supported by only three hooves, as I stumbled down them and alighted upon the cold ground of the tunnel. Though there were lights placed at regular intervals down either length, still the darkness was palpable in the air, solidifying in my lungs, closing them up and causing me to pant.

To the right, down the length of the tunnel, there was a long procession of Royal Guards, all clad in identical golden armor. In his mouth, each carried a bull’s-eye lantern swaying back and forth in time with his firm canter; long beams of light shot erratically across the tunnel, washing over the hewed walls of the mountain, alighting briefly on the metal of the train and reflecting into my eyes; and with each undulation, their rows of spears glinted, erect, poised, quivering.

I pressed myself flat against the train. With firmly-pressed lips, I held my breath as I watched the light from beneath my eyelids, first blinding me, then fading away, implicating me then ignoring me, playing with me as though I were a mouse; it, a vicious cat.

A sentry stood outside on the same side of the train as I, no more than one car length away. He was too far away to be considered a part of that procession, and he carried no bull’s-eye lantern, only his spear. His air was too different from the others I had seen for him to be one of them.

When he whipped his head around, I saw the dark red mane. I saw Foil.

I ran away from him as fast as my limp permitted. In the distance, a pinpoint of light shone, not a harsh yellow but a faint blue.

I limped until I thought my luck had run out. I jumped through the door of another car to hide. But through the muted voices of the passengers inside the train, through the heavy tread of the Guard’s march, through the pulse in my ears, I could have sworn I heard a voice call out to me.

It was only when I sat down on the floor of the car that I realized the strain that that short run had taken on me. I collapsed, panting with exhaustion, fuming at my weakness; and all the while my off foreleg throbbed beneath its gauze which was now collecting soot. Behind the train’s walls on either side loomed the mountain not a score of feet away, pressing in, pushing out the air, absorbing the light.

I was cornered. Even if Foil hadn’t seen me, it would be only a matter of time before he would catch up. Even if I were to take, limp and all, to the end of the tunnel, even if by some miracle I were to elude them with my distance, others would undoubtedly see me when I emerged on the other side.

I looked around the car, at what I thought would be the last environment in which I would enjoy freedom. Should it not have been the open air, somewhere I could have one last flight above the clouds before being grounded forever? Instead I was treated to only metal, and not a very pleasing variety: A thick, dull metal covered with a multitude of glass bulbs in which were needles gesturing toward countless symbols and scratches, all this surrounding a grate with thick slits protecting an orange glow.

And to top it off, what was I sitting on? Could I say the gentle green blades of grass planting their roots in the rich-smelling soil, the setting that should have adorned my last repose in freedom? Oh, were it only so! Instead, the grass was a metallic plain, and its soil were black rocks of varying size, but all identical in composition, all giving off that acrid smell of sulfur . . .

Hold . . . sulfur?

I picked up one of the rocks that were scattered across the floor of the car, brought it to my nose, and inhaled deeply. The smell nearly made me retch. But the odor was unmistakable.

Coal! I was in the engine room! That grate with the orange glow behind it—that was what powered the train!

The furnace was off and unfed because we were in the tunnel. But what would happen if it were fed? Smoke with no place to vent . . .

If I were to feed the engine, I could limp my way to the end of the tunnel before the smoke obscured its length, and I could escape—toward the open air, toward freedom!

I would have to be quick, light on my feet, careful where I stepped, and deliberate in motion. If I left too soon, they would see and catch up with me before the smoke could plunge all into darkness. But if I left too late, I would be blind and have no recourse.

That was it, then. I lit my horn, used my magic to open the grate, and posed it in readiness above my target.

I turned my head away, my feet posed to jump from the flames that would leap in protest as soon as the primed rock was released. Here I was, on the edge of a moment that would set a series of inexorable events in motion. Before me stood not a furnace but the first entity in a chain of cataclysmic causes. It would be only a flick of my horn; then there would be fire, then smoke, erosion, now everything that once stood nothing more than a medium for the course of the flames, and I would not look back at that conflagration lest the smoke and the fury overwhelm me, growing in an unchecked expansion, twisting higher and higher over the earth.

The wisp of a whim crossed the highest altitude of my consciousness. So innocuous, so gentle that it could barely be felt, yet it was substantial enough to cause me to set the piece of coal back down and thrust my head out of the car. The risk to me seemed at the moment to be less important than what I wanted to see.

There, in the distance, detached from his platoon, standing in the lonely tunnel, was Foil. He still didn’t have a lantern; but now he wasn’t carrying his spear. Neither had he his helmet; and his red mane still displayed its rich color in the somber light, swaying around his neck with graceful but decided sweeps when he turned his head to scrutinize the various nooks of the train. The tunnel lighting passed across the side of his face in waves with his gentle movements and every so often caught the depth of his eye, which shone to me, naked in its keen purity.

I ducked back inside the engine car and shook my head. He was a pony, just like the rest, an inferior, one who was chasing me, one who would subjugate me if given the chance . . .

I tried to picture Foil with a menacing growl and eyes afire, his spear tip trembling against the fleshy part of my neck, as I’d once seen him a few days ago. But I couldn’t. All I could see was the creature I’d lectured to for hours that had brought me no end of enjoyment, both for me and for him. All I saw when I called the image of Foil to my mind was a student, vacant in regard to raw information but eager to fill it with any word of wisdom that he could manage to latch onto with his unrestrained enthusiasm for knowledge.

A student. Yes, indeed he was, I concluded. Not only that, but his ability to listen, to pay attention, and to ask relevant questions covering topics I’d omitted in my haste or in my mistaken presumption that he would not have been able to understand them surpassed that of my common rabble, whose indifference was visible in the drool that fell from their outstretched mouths during my lectures.

I shook my head once more as the thought passed as quickly as it had come.

Why was I so far away from home? Why was I in a land filled with such strange creature in the first place? I knew the answer: my family. Yes, everything I did in this land had been and was for them. And they were dispersed—but all the more reason I should help them.

I raised the coal block to the flames. I hurled the black mass, and though the flames leaped up and out of the grate, passing so close to my face that I felt them touch me with their heat and wrath, I could not feel the warmth. The chilliness of the dank mountain seeped through the walls of the train as easily as it seeped through my skin.

I sat back on the floor as the furnace burned, using the fleeting moment I had to catch my breath and to prepare myself for the run I would have to make which would no doubt be the most exerting one of my life (due in no small part to my lame foreleg). The dials in the bulbs shifted imperceptibly clockwise, each heading to an area of its disk shaded in bright red. I was too far away to read the labels on the meters, but I didn’t have to understand that the red represented hazardous conditions. Red is the interlingual color for hazard; one need not to understand a society’s language to understand that he is being warned with the color.

The dials climbed. How agonizingly slowly did they climb!

What to do with these minutes in which I had nothing but my thoughts? Check my premises. Check my plan of action: Wait for the furnace to heat. As soon as I see the smoke layer, as soon as I taste sulfur, I run to the end of the tunnel. I run until my legs burn. I run until my lungs burn. I run until I can feel the sun on my face, grass beneath my feet, and clean air in my nose. And, after that, I would take the next steps to ensuring that the pegasus, whom I’d managed to take with me this far—

I ejaculated a shrilled curse as my eyes went wide. I heard it bounce off the walls of the tunnel. A minute later, the curse came back; the words sounded different from when they’d left my mouth but the fervor was unmistakably mine.

The pegasus! My prey! I’d completely forgotten about her!

I leaped to my feet. No sooner had I run out the door through which I had first entered the engine than I had to duck back in again, for the platoon was advancing through that stretch of the tunnel, a unicorn at their head sending out clouds of the magic that I’d seen earlier. I tried the door on the other side—another platoon, no smaller than the first, on the other side of the tunnel, a unicorn using the same magic at their head as well. Their individual footsteps resounded through the tunnel in unison; and with each beat, so too pulsed their revealing magic. It threw itself against me, one intolerable bombardment after another.

The unicorn magic bit into my head with a freezing seizure, and I could hold my facade no longer. An instant, disorienting change surged through me, not a gradual one as it usually was; it was as if the magic had flayed the affected skin, leaving me exposed.

Hovering as best I could on my good wing, I reached up to unlock the escape latch on the top of the engine. My wing, exhausted, gave out the moment my near foreleg established purchase to a grove on the roof. Hanging from the latch on one hoof, I swung in that wise for an agonizingly long time, my hind legs flailing under me as I tried to pull myself through.

At length, and through exertions powered in small part by my frustration at my bodily frailty, I managed to pull myself through the trap door and onto the ceiling. Already I could smell and feel the heat of the exhaust being vented behind me from the train’s funnel. Trying to control my breathing and to push the intimation of the suffocating panic out of my mind, I crouched on the roof of the train and crawled back in the direction I’d come, as I mentally recounted my steps to remember which car I’d left the pegasus in.

Conical beams from the bulls-eye lanterns darted ever more violently around. The fire scintillating in the lanterns imparted to the air a violent flashing, the innumerable cones forever rebounding off each other, and when they hit the glossy mountain walls, the crystals flickered with the flames, evincing a caprice almost characteristic of sentience. I crawled with my eyes shut, blind, lest the light reflect off my opalescent irises. I held my injured leg against me. My crawl was more akin to a hobble. I moved like an ant, pausing and pressing myself flat to the roof whenever the light’s vicissitudes carried them within an inch of me. The rays lapped against me, burning the extremities of my body, as if it were the light and not the flame that carried the heat.

The ponies passed on both sides, surrounded by their disembodied sentinels. Each had his head turned in a different direction, as though they were trying to use their brightly colored helmets to reflect the light in all directions. Their eyes scanned the walls, the train, but never directly upward, not up toward the black vacuum above, where the mountain loomed out of sight into the darkness and where their sentinels couldn’t penetrate. Behind, to their sides, and in front, they were looking for where they could see the light absorbed by black skin, the infallible indication of the encroacher that was I silently moving, pausing, and listening, avoiding their cleansing beams whose tails fell through the air like meteors.

I lay still, watching the light flicker from beneath my closed eyelids, not daring to move or to breathe; until, at length, my fleshed seared me no longer, and the white beneath my eyelids ceded to the original black. I exhaled the breath I’d been holding only when the sound of footsteps continued down the length of the tunnel, behind me. Testing my magic (much like how one tests a piece of flint for its potential to make a fire), I found that it once more swirled freely and easily. I transformed back into my unicorn form before I slipped off the top of the train and into the car I’d been on.

It was by sheer luck that the car I entered was the one I’d left the pegasus in.

“Errenax!” she gasped, when she saw me. “Where have you been? You don’t know how I worried! But you’re back now, so that’s—”

“Listen to me,” I hissed into her ear, grabbing her hoof with my own. “We need to go.”

It was not the braking of the train and its resulting invisible force, not the sentries, not their lanterns, not the revealing magic, nor my absence that had perturbed her, but the two sentences I had just spoken.

“Is there a problem?” she asked. “What’s going on? Why are you sweating?”

“Don’t ask questions,” I said. “Follow me.”

She didn’t budge. “If . . . if there’s a problem, maybe we should . . . you should tell somepony in charge. I think the conductor passed a little while back. Maybe you can find him and—”

“I don’t have time to argue!” I pressed, my voice a low growl. Between the thought of the sentries closing in, the thought of her resisting me, and that fine point wherein the tone of my voice was powerful enough to be commanding but quiet enough to not arouse suspicion from the other passengers I had to achieve—all these factors pulled at my mind as hard as they pulled at my fear.

“Do you not remember the first time you saw me?” I continued, when she only stared back. “Do you not remember how you encountered me? I was cold, wet, injured, destitute, and on the verge of insanity—I was dying. And you saved me. You saved my life. You gave me a blanket and dried me when I was wet. You gave me food when I was starving. When you saw that my leg was sprained, you splinted it.” And here I raised to her my off foreleg, the once-pinkish gauze now black from the layer of dirt that it had collected from the tunnel.

“But one cannot help unless he whom one wants to help will accept him,” I went on. “The invalid must accept his savior. How does that expression go? You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make him drink? I drank when you led me to water. I was reluctant at first, and your first touches pained me, but I accepted them, and then I was healed. But I’d had to trust you first. And now, you need to trust me. You saved my life. Now, I’m going to return the favor. But you must trust me!”

Sulfur filled my nose as she pondered her decision. I stood waiting, my legs shaking, my eyes watering, while I fought the urge to grab her by the wing and pull her with me.

She looked around the car. The passengers were twitching in their seats with that restless anxiety a creature experiences when it’s cornered. They mumbled, each one voicing that anxiety—none knowing what it was. In the air hovered a thick but invisible feeling of panic.

The pegasus looked back to me. She swallowed nervously, gave me the bag that I’d left with her, and pulled the cinch of hers around herself.

Not before a slight pause after these actions, she stammered: “Alright . . . I trust you.”

“Good,” I whispered. “Now follow me. Hurry.”

She trotted up next to me as I passed the way I’d come the first time. Our footsteps were drowned out by those of the Guard echoing around the tunnel.

“Don’t argue,” I whispered. “Don’t ask questions; don’t look at me for clarification. Stay close, and let’s go.”

When we approached the door, I motioned for her to stop. Gently, I leaned my head around the threshold and into the tunnel. On either side of the train were a column of guards. There were more of them now; all of them moved in that systematic inundation, and their lanterns were scanning the roofs of the car and the walls.

The top of the train wouldn’t be an option. I swore yet again. Though I wasn’t in the tunnel, I thought I heard it rebound back to me again; and it sounded differently but still carried the same intent, just like last time.

I turned at a noise behind me. The pegasus was coughing. Her squinted eyelids could not hide her bloodshot corneas.

“You said you trusted me and would do anything I asked,” I said to her.

She coughed. “Yes,” she said, her voice raspy.

I looked around the corner one more time, waiting for the soldiers to turn their backs. “When I move, you—”

At that moment, the guards turned and I had dashed around the corner and crawled to the underside of the train. I didn’t need to look back to make sure; the pegasus’s light footsteps were unmistakable.

“Crawl,” I whispered. My voice scarcely penetrated the thickening air.

I began to move, my stomach scraping the jagged gravel between the crossties, toward the light, which I could still see at the end of the tunnel. But instead of growing larger as I neared it, as it should have, it darkened and shrunk, as though a fog were descending on me and my mind.

On either side of the train, a flurry of thunderous, armor-plated hooves fell, now a blizzard, resonating their force through the ground. An image of a hoof staving in my head flashed briefly through my thoughts, only to be thrown out as the sound redoubled. I imagined the engine’s gears engaging the burning furnace and sending the train forward, its wheels rolling, catching my tail, and pushing an inexorable weight and pain onto me, the only recourse to scream in those agonizing seconds as it impersonally crushed the life out of me. My head collided on a metal bar extending the width of the train’s underside, rattling my teeth and sending a shrill ring through the tunnel. But that sound—along with the sound of my scream, and the rasp of my breathing and the pegasus’s—died upon touching the air, as the light swept the rim of the shadowy black rectangle the train cast around us. I curled myself into a ball. My heart pounded as the light skimmed the extremities of my space. Were I only to extend my forehoof a millimeter out of the darkness, make a small movement, a twitch in the dregs of a whim—I would be blinded, flicked out of existence in an instant, without even a transitory period for me to realize what would kill me. A millimeter away was the difference between safety and immediate annihilation.

The light shook and moved away as gasps filled the tunnel—powerful, forceful coughs that permitted me to hear nothing else. It sounded as though the mountain itself were choking. Behind me, the pegasus scarcely breathed. She let out a dainty cough, but still her sounds of life pressed on. The taste of the air was now clearly distinguishable, and it burned my throat.

I had not planned that the end of the crawl to the front of the train would take us out onto a stretch of track free of guards, but—yes!—the track stretched toward the light in the distance, obstructed by nothing but an ever-thickening haze.

I emerged from the bottom of the engine and stepped onto the track. When I’d gotten my balance, I turned around and helped the pegasus clear the engine’s bumper and get to her feet.

“To the end,” I hissed.

I galloped as fast as I could, limp permitting. All the while, I felt the cloud behind me, reaching out toward us with its tendrils and tearing at my chest with its grasp. But still we ran, coughing when need be, neck and neck for most of the length. A new life rose from within us, further powering our flight when we breathed the cleaner air entering our nostrils and touched the light stretching its rays ever-brighter and longer toward us.

Would that we make it! Curse this mountain! Already, I could feel the outside, and I imagined the plains, with nothing to impede the movements of my hooves, or my wings, the open air to me . . .

I screamed as my motion was suddenly halted. My croup was caught in place, and I fell face-first onto the ground. When I tried to pull myself free, pain flared sharply on the roots of my tail.

My tail was caught!

The pegasus slowed her pace in front of me. Now, I could barely see her. The cloud raced on past me, filling my nose and my mouth, and continued to race toward her. Her vague shape in the smoke turned ever so slightly, as though she wanted to check back on me.

“Go!” I cried.

No sooner had she turned away than the cloud rushed to fill the space she had left behind her.

I could no longer see anything but smoke and dust. I couldn’t even cough anymore; I had not the energy.

As quickly as I’d been arrested, and as unexpectedly, the restraint lifted. The smoke clouding my thoughts as thickly as it did over my eyes, I could not run forward. I stood posed, still, for a brief moment, in a state of confused awe, knowing not what was behind or forward, unable to choose one.

In that moment of indecision, an imperious weight fell from above and brought me prostrate onto the tracks. It was not pain that made me scream inaudibly through the muting fog; what I felt from its first touch was its immovability, as though there were no number of creatures, no amount of living strength that could relieve this crushing mass, as if where it landed were where it would stay—the only force that would be able to move it an inch was the earth, the same force that in times of geological tranquility would take a century to move a glacier, a millennium to erect a mountain, but only a second in suffocating wrath to bring that same mountain down in blind fury upon me, as it did just then.

I was just able to turn my head to the side, to cast my eyes up, to see the void that had sent the stone to mark my final resting place.

There, from out of the curling black air, inches from my face, gleamed at me a wide, shimmering row of teeth locked down in rage. The shape of a nose, then a muzzle, and a mane whose red could still be made out in the opaque smoke, a brow whose furrows were drowned with purpose, formed from the obscurity, yet were still a part of it—and finally, two eyes, glimmering like bull’s-eye lanterns, sparked forth from their embers his ulterior intelligence, watching me, judging me, and finally damning me. In that moment, my impending asphyxiation didn’t matter to me anymore; my fear of it had been replaced by my dread of that discernment, too sharp to be anything of this world, yet too familiar in method to be anything but terrestrial sentience. And I knew that it had been lying dormant only so that it would be able to awaken for this very moment, to be fresh and unbiased for a last effort, to stamp me out of existence with full certainty.

Foil didn’t move. When I tried to squirm, I moved no more than if Foil’s body had indeed been the mountain itself resting on me. He snorted, a deep, fierce, firm exhale, sending two clouds of smoke in opposite directions from his nostrils, and his eyes pulsed back with their light in response. My near leg free, I was able to turn just enough to strike him in the face with its cannon; but where I should have felt skin and muscle, I felt only stone. Foil was not flesh to be molded or subdued; he was a living rock concealing an intellect with a fire more ardent than any ever held by the highest moral philosopher, a warrior who knew that fire’s purpose and how to wield it, a judge with a body more immaculate than marble.

Still he stared back at me. It was not rage that marked his face; it appeared that way only to me, who was under its dominion. Those eyes which did not deviate from their mark, those immovable teeth, that iron stare—it was knowledge. Pure, unadulterated knowledge of something broken, a certainty of wrongness; and I felt, with him upon me, my mobility completely at his mercy, his power, and his ability to exact his justice upon that wrongness . . . upon me.

The light of his eyes blinked once . . . and then were gone. He no longer actively resisted my movements with those of his own. On top of me was nothing more than rubble now, heavier than that which had subdued me in Canterlot: heavy in its lingering warmth, in its rigidness; and this weight, lying on me, pressed more heavily on my mind than it did on my body—but now, there was no one to pull me from it and give me water.

With my back legs, I kicked as hard as I could. Foil moved a few inches as I struggled again and again. Each time I squirmed, he moved a smaller distance, as my strength diminished. In my exertions, I gasped for more air and coughed when my throat received only more of the caustic sediment. My lungs burned with each breath, my legs and back with each convulsion.

One last breath, one last kick, and once more I squirmed, turning upon myself, tangling and twisting my ribs . . . and he shifted once again, one last time, just enough to allow me to rise on my near foreleg. Foil slid off me as off an incline as I stood, but it seemed that he fell slower than if he had been inert, as though there were a conscious force lingering a little while longer and clutching at me while it still could.

The spinning of my head made me unable to orient myself. I ran blindly in the direction of my desperate first step. No light promised to me the end of the tunnel, nothing but shadows all around. With a blind rage, I shut my eyes and made my last exertion. When my legs failed, I collapsed, the gravel between the crossties cutting into my abdomen as I slid forward on my own inertia.

The heat of the smoke changed in attitude; I felt it as though it were the heat of the sun. Dying in a black tunnel, trapped and drowned, I permitted myself the feeling of sleeping in the open air, with the sun on my back, clean air in my lungs, a constant movement carrying me forward, away from the blackness, toward repose.

*

The sun was so bright that I could barely open my eyes. I was alive, undoubtedly; but I could not believe it.

“You’re awake!” said the pegasus.

Sweat ran down her temples; panting punctuated her sentences. At that moment, I gained control of my faculties and keeled over; the first order of business was to cough until the sulfur was gone, until I could no longer taste it. But here we were; there she was—out in the open, alive, safe.

I wiped the drool from my lips with a fetlock and sat up on my haunches, a bit lightheaded, but overall good in health, my thoughts sharp once again. I knew exactly where I was, fixed once more into my proper state of mind: on a strip of track extending toward the horizon in one direction, plains all around me, trees bordering their outskirts.

When I noticed that the pegasus was still staring at me, I grabbed her forehooves with my own. I ignored her reaction of shock as I looked at her; I couldn’t hold back an unseen but nonetheless real feeling of profundity, which flowed from me to her.

“Thank you. Thank . . . thank you.”

She turned her head, her ears pinned, and her mane fell over her face in such a wise as to appear to have been a practiced act. “It’s alright,” she murmured. “You would have done the same for me. Anypony would have done the same for anypony else.”

She started down the track. “There should be an outdoor train stop somewhere along the line not too far from here. We’ll be able to get help there.”

I took my time getting to my feet, thinking that she’d wait for me to follow. But when I’d shaken the dust off my knees, she was already a silhouette in the distance, still walking, but with a steadfastness and haste that seemed too firm to be casual. She didn’t turn back to see if I was following. She moved as though she were leaving the world behind.

When I realized that she was not waiting for me, I limped after her. Only once did I look back to the mountain. Instead of a train tunnel with its roughly hewn roof, there was a featureless maw, curls of its black breath twirling indolently around its overhanging teeth and dispersing without a trace into the surrounding air.

So... he just murdered like 200 ponies to avoid getting caught, and Fluttershy is okay with that?

So... apparently Equestria uses some really highly condensed coal-like substance as fuel and has really temperamental tunnel ventilation systems in this universe. I must admit, I am very puzzled. I mean... seriously, the addition of one lump of fuel did that? I think I really need an explanation for this to continue enjoying this story, sorry. I can try to come up with one on my own, but I'd really like to hear yours.

edit: Okay... pending your explanation or a better one, I'm going to pretend that the engine was oil (or a similar liquid) fired and Errenax was able to find the fuel valve. It's still a bit hard to believe that the engine crew didn't either shut it off or just drive out, particularly given that this locomotive appears to have an enclosed cab, but maybe the guards took them too far away for some reason. It's also a bit hard to believe that the guard selected a tunnel with such poor ventilation to stop a train in, but... maybe the ventilation system was damaged in the attack? I don't know. It's plausible enough for me to not unfavourite the story, at least, which would have been a pity.

To be fair I don't think he even suspected the train would crash. He just wanted smoke to conceal his escape. "everything that once stood nothing more than a medium for the course of the flames" wasn't literally predicting the train to catch on fire somehow, but instead a metaphor for how upon igniting that engine, Errenax would be blatantly alerting the ponies to his presence and, if he escaped, lost in a mountainous wilderness with a broken leg. He was surprised as anyone else when the tunnel collapsed on top of him, and he wasn't savvy enough about coal technology to know that the smoke is anything more dangerous than a sulfrous smelling concealing cloud.

That moment of second thoughts inside the engine and the struggle with Foil were probably two of the finest written portions of this story.

Then again, I can find precise sections of masterful writing in almost every chapter! Carry on.

Errenax, you insufferably intelligent fool, what have you done this time? Who have you ruined to escape the ruin you brought on yourself? What more can you get away with under the veil of your childlike naïveté?

If only the teacher could learn.

...with that said, I will clarify that I actually love Errenax as a character. I was just feeling a bit poetic~

I have to admit, in this entire story, this was the first time I had trouble understanding the action. The purple prose actually did get in the way. So I need someone to confirm what happened.

Errenax snuck to the front of the train, set it up to fill with smoke so he could make his escape, went back to get Fluttershy, crawled back to the front of the train with her in tow, then Foil caught him at the last minute, pinned him down, Errenax knocked out Foil with one blow to the face, and then tried to escape, before choking on the smoke. Fluttershy came back and dragged him out to safety.

Much as the above, I find myself at a loss to discern whether that was Foil or not that had pinned him down.

4578937

This is how I understood it, though I think it was the smoke that got Foil rather than Errenax's strike.