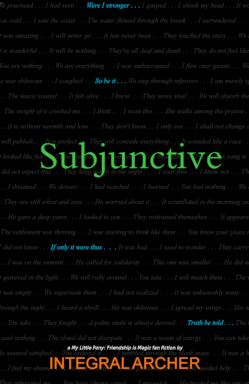

Prologue

Were I anything less than patient and observant, this whole affair would have broken asunder long ago. What were five more minutes of patience? Five more minutes to savor the moment.

I was sitting outside of a café that I had grown rather fond of during my four months in the capital city. From a porcelain chalice, I was sipping a rather pleasant-tasting beverage which was called coffee. Spread out on the table in front of me was a piece of low-quality paper, upon which was printed the meaningless drivel from the day before. I was pretending to be interested in its contents.

It was called a newspaper. Ah, I thought, as the realization struck me—newspaper. What a word! How had I not realized that earlier? What an intuitive, wonderful portmanteau, and the result was a word that expressed not only what basic elements composed the object it referred to, but also expressed the purpose of the said object. I smiled at the thought. I’d always enjoyed words whose etymology could be gleaned just by speaking them once. They were little bits of consistency in my world of irregulars and defectives.

Occasionally, I craned my neck skyward so that I could see those blindingly bright spires on the top of the royal palace’s main tower. The mystic, bubble-like shield surrounding the city imparted to the sun’s rays a pink tinge before allowing them to reflect off the edifice and inlay themselves in my fur with a stickiness like tar. The insulating down that covered my entire body engulfed me with an overbearing heat—a discomfort, I had realized too late, that was peculiar only to pegasus ponies.

Uncomfortable, yes, but what were five more minutes? Five more minutes of repressing that ulterior anxiety lest it manifest itself.

My vision was suddenly obstructed by a large body. I looked up and saw a white pony in the traditional golden armor of the Royal Guard. He was standing in the way of my view of the structure. The light reflected by the spire now cast down behind him in oblong rays, covering his face in shadow. He grimaced menacingly and bellowed: “Citizen, you’ve been in that spot for over two hours now. Explain your behavior.”

I smiled and took another sip of coffee. “Just enjoying Her Majesty’s palace and the sun. No crime in that now, is there?”

“No loitering. Move it along.”

I chuckled and put the cup down. “Oh, come now, Foil. I clearly have a purpose here. Are you seriously going to make me move?”

The pony’s features relaxed. With a forehoof, he removed his helmet, revealing a dark red mane, and wiped the sweat off his brow with his enormous fetlock. “I’m sorry, Errenax. I’m just on edge. We all are.”

“Oh,” I said, my voice dropping in intensity as I attempted to find that appropriate tone of sympathy without overdoing it and bleeding into ironicalness, “I’m sorry to hear that! Are they stretching you thin?”

“They’ve extended all our patrol routes,” he said, sitting down in the chair opposite mine and leaning closer to me. His eyes were bloodshot. “I’m walking nearly a marathon a day now. Would you believe it? Yesterday, it took me three hours just to complete one round. There’s just not enough of us to patrol the city!”

“That’s unfortunate,” I replied, as that was what the situation demanded I respond with.

He groaned. “The sooner this whole wedding thing is over, the better.”

“It seems to me,” I said, “that the most practical argument against the efficacy of the police state is sitting in front of me at this very moment. Look at you! How do your officers expect you to be able to identify interlopers, to merely do your job, if they insist on stretching you as they do? It seems to me to be impossible.”

“Shut up,” he said, raising his eyelids halfway. “I do not come to you to hear of politics.” A noise that sounded like a mixture of a snicker and a gasp made its way out of his throat. “But . . . police state, you said? Surprisingly, that’s not completely off the mark. Did you know the city is technically under martial law? If I wanted to, I could arrest you, right now, for no reason.”

I smiled. “Is that right? How did that come to be?”

The sentry glared at me. Then, in an instant, he struck himself erect, stared straight off into space, and said in a monotone: “The Princesses of Equestria, by and with the recommendation and consent of the prime minister and his parliament, decree that unilateral power be given to the Royal Guard for a duration of time subject to Their Majesties’ pleasure, for the purpose of ensuring the lasting security and peace of—garbage, garbage, garbage, I’m holding you without reason. Do not resist.”

He let his head fall. He did not see me twitch when the impact of his helmet resounded with a crash against the glass surface of the table.

A cry rippled through the air, and I reeled from the unexpected shock. As I strained to assuage the magnitude of my impulsive cringe, I watched the pony, his head on the table, as he breathed heavily in his half-sleep, in his full unwittingness. When I was sure he hadn’t noticed, I turned my head under the pretense of a cough. Instead, from the depth of my throat, I let out a shrill of a similar frequency in response, high enough such that the pony sitting across from me and the ponies walking on the streets around would not have been able to hear it, much less understand the language in which the words were spoken: “Say that again, my brother.”

“He suspects you, Brother Commander!” came the same voice. He was one who had not come with me initially, but I could tell by his panicked pace and vacillation of tonal frequency that he was young and perhaps had never taken part in something like this before. “Your brother lieutenant translated what the beast said for me, and I see only too clearly that we are lost! Be it confounded!”

“In jest, brother. In jest,” I replied. “In their language, tonal variation is as important, if not more so, than the words themselves. If you knew my brother lieutenant as well as I do, you would know that his translation philosophy is one of literalism. Have you not heard me lecture on the poison of that philosophy before? Wait for her signal, as you have been so patiently doing.”

“And when comes that signal?”

I tapped the sentry on the shoulder with a forehoof. “So, I take it the wedding is on time?”

He turned his head sideways to see over the edge of the table. Out of a pocket on his armor, he pulled a watch, and indolently raised it such that it just barely met the plane of his eyesight. “Ahead of schedule, actually,” he said. He let the watch fall. “It’s happening now. And in a few moments, all my grief will be behind me.”

“Now?” I gasped.

“That’s what I said. Don’t shout.”

I turned my head again. “Now,” I shrilled.

Instantly, the buzzing in my head became ecstatically, deafeningly loud. As my head began to spin in the giddy miasma of sounds, the impulse to share their jubilation almost overpowered my desire to stay clandestine . . . but no. I listened, biting my teeth at the pain of my imposed, strained silence, while my body shuddered as the ground does when torrents of magma rush through its veins toward a mountain’s summit during the onset of a volcanic eruption.

The sentry rolled his head over. As I stared at him, I sitting erect, he with his chin on the table and his eyes up, staring back at me, the voices in my head grew in magnitude, both in word and in tone as rumors and suppositions piled one on top of the other.

I looked around me at the city, its buildings. I marked its inhabitants, ponies, a myriad of colors endlessly mixing with each other on the street as they walked among themselves. They talked with each other as they had always talked, as if there were no presence looming over them, bearing down on them from above.

By now, I could hear the shrills more acutely than I could hear the voices of the ponies in the city. But still I watched the ponies talk, watched their mouths move in speech. I smiled as the general din of the city faded to the shrills. For I knew the essence of that din, what it meant, what it represented: the din of a city was the pulse of its heart, its language its blood, a million tributaries of voices feeding the interweaving of a complex, delicate structure of streets. As the ponies’ words faded around me, the evanescence of their language, of them, and of their blood evinced itself to my ears.

And, more clearly than ever before, as the sentry’s ear errantly twitched, I saw the wall dividing us from them, dividing me from the pony, a barrier not just of language but of thought, of deed, of method. I sat up straight, ascendant and lofty; while he lay prostrate, abject and downcast. On my side of the wall, it was clear. I could see what encompassed all, us and them, and I looked upon the sentry; while, on his side, he saw only my facade, the immediate reality. To him and his kind, what mattered were only the celestial laws that governed the rising and setting of the sun, what was in front of them, and what they could immediately perceive and know. What occurred outside the realm of reality, what lurked in depths privy to none except those in the realm of the possible and the supposed, mattered not to them, and he looked at me as if there were nothing else to consider, his eyes glossy, his tongue leaving a puddle of drool on the table.

My hair stood on end. How could he carry on thus? Even if he couldn’t hear the shrills, which were now at their climax, could he not even feel it? Were they that insensate that they could not feel the air tingling with anticipation?

At length, he stood, stretched, and yawned. As he picked up his spear, I saw his lips move. But all I heard were the shrills in my head, their suppositions dancing round and round, following only themselves in their gaiety, such that I could not hear what he had said.

“Be you silent!” came the imperious injunction—and the voices vanished in an instant, such that it left a vacuum in my head. Her shrill and style of speech were distinctive enough that she could be recognized out of the crowd. “I will give the signal. Be patient.”

“What was that?” I said to the sentry, as the concrete world resumed its place in my ears.

“I asked when you were leaving,” he replied.

“I’m flying back later tonight—that is, if your friends let me leave the city.”

“So soon? Ah, a shame!” he said, shaking his head. “You’ve never seen me without my spear, and I’ve never seen you without your reading glasses! A friendship isn’t complete until both parties have spent leisure time together. What about having a drink together on a Friday night after work, as would be proper between two friends?”

“Well,” I said, sharply raising the tone of my voice, as if I were considering his proposition, “I’ll see what I can do. Perhaps I can stay for a few more days.” I raised my cup to him. “I’ll find you when this is all over.”

“Thanks,” he said, “I’d love that.” He brought his eyes skyward as he sighed. “And, if I don’t see you again, I have to say . . . I’ve really enjoyed talking to you these past weeks.” He laughed, and there was an odd note of the slightest sorrow in his tone. “Look at me! A dumb Canterlot sentry who skips like a schoolfilly to this café every day to receive personal lectures in linguistics from a Fillydelphian scholar—and you don’t even charge me! What are you, Errenax? Not a teacher from this world. No teacher has ever been able to hold my attention as firmly as you have; no teacher has ever managed to make me care about a subject he wanted me to care about. But you speak so passionately, so enthusiastically! Nopony could help but become intrigued.”

“You should tell that to my students,” I replied. “Maybe that will help them stay awake.”

At this, the pony’s fatigued eyes shot open, and he convulsively clutched at his spear with a forehoof. The red vessels in his eyes throbbed. “Brats!” he shrieked. “Rude brats! Take me to them. If they refuse to learn a lesson through you, they’ll learn one from me! Do they not understand what they’re missing?” He closed his eyes and unclenched his jaw. “When I listen to you, I wish that I hadn’t dropped out of high school. I envy your students.”

“I try,” I said, with a toothy grin. “But you shouldn’t be too hard on yourself. You’re a soldier in Their Majesties’ service, and their lives depend on your ability! It’s quite a prestigious and honorable career, all things considered.”

He furrowed his brow. “Don’t patronize me.” With a bowed neck, he sighed, and the lethargic undulation of his head in the feeble breeze shook loose a drop of sweat from his left temple. “Finish up your coffee and move along,” he said to me, when he had finally managed to hold himself straight, albeit with some visible trembling. “The next patrol won’t be as forgiving as I am.”

“I will.” I smiled as he nodded once more to me. “Hey, Foil!” I said, as he began to move on. I decided to close the conversation with an indicative by saying: “I’ll see you later!” And I added, for good measure, the two most ridiculous imperatives that existed in their language but which seemed to assure them nonetheless, blind as they were to their banality: “Have a nice day! Be careful!” I’d spoken as though the first were in his control, and as if he weren’t already planning to do the second. And as if I’d really meant those things.

When he at last was out of sight, I knew that that conversation had marked the end of our relationship as it stood, the end of my lessons to him, the end of his education. It had marked the end of his enthusiasm, and, consequently, had marked the inevitable augmentation of mine.

In the silence, the air around me pulsed with an anxiety that swelled with every passing second. I held my breath, waiting for it to burst. As my teeth chattered, I looked around me: still, the ponies walked back and forth down the street, and their insipid conversations droned on, unchanged in their tones.

Such is the relationship between the host and the wasp. The former carries on his life, unwary that his intestines have been inlaid with the latter’s bulbous eggs. The host eats, while the incubating wasps quiver silently as they slumber in the warm, membranous flesh. But at the critical moment, when the eggs are ripe, when the infants’ legs ache from being curled upon themselves for far too long, they go silent, just for a second . . . and in unison, on the impetus of a jussive issuing from the egg that will hatch a born leader, they . . .

I heard a pony scream in a higher frequency than I had thought possible for their vocal cords. No sooner had I turned my sight upward than the impediment shattered. The city seemed to gasp like a creature so long submerged in a murky pool bursting to the surface and expecting the liberated air. And the city shrieked when it felt entering its lungs only the expectant wasps.

As they descended, the firmament, at first only lightly punctuated by an erratic darting of black points, seemed to close in upon itself as they came into eyesight. The open air, the sunlight, and the sound of the wind ceded to wing gusts, glistening canines, and shrills. At this sound, which was nothing more than the words of their language preceding them, the ponies screamed as if these shrills were ravenous war cries.

The suffocating fur fell away, first from my head, then from my torso. I felt, for the first time in four months, the breeze through the holes in my skin. I relished the return of my old, thin wings; for the large, bulky pony wings had been so hard to flap; and, as I twitched my true wings ever so slightly, I felt as if just a few strokes from them would be sufficient to allow me to sail effortlessly through the air. The sun no longer felt hostile to me; on my black skin, it felt good, and the merciless heat that had been trapped under my affected feathers had been carried away. That feeling of sublime comfort returned to me as I ran a forehoof over the raised skin on the back of my neck and over my horn.

The ponies ran while I stood riveted in conviction. With my eyes closed and my mouth open, I laughed as the wave of the swarm’s shrills rushed over me, and it purged any pony inclinations that I may have picked up in the previous months, leaving me pure and free once again. With the return of my body came the return of my spirit, too long suppressed, too long desired, liberated only now by the return of my family.

Though they moved with great haste, I walked, a part of them, one black form calm and composed in the midst of their furor. Their task was just beginning; and, for them, it was a time for exertion. But, for me, it was a time for repose, a relaxation made all the more sweet by the knowledge that what I had done before was consummate, and the proof of that flew around me in the form of my brothers and sisters.

As I was scanning the erratic movements, looking for a face I might recognize, I spotted a female who, despite being pushed and shoved by the faster ones around her, continued on with a determination and a steadfastness that was remarkable. “Sister!” I shrilled, as I approached her “I am your brother commander! I am the one who delivered this settlement, rich with its treasures, unto you! This is my gift to you—to us!”

She turned with fangs bared, with eyes afire, a snapshot of her in the ecstasy of feeding. But when she saw me, instantly, she relaxed. She ran toward me. When she nuzzled her forehead against my neck, her horn flashed for a brief instant; and in my mind I saw hunger and longing, despair and destitution, turned to relief and salvation, joy and exultation—her emotions, her gift to me, the feeling of her desires now being satisfied, and she wanted me to share in them.

“Brother Commander!” she shrilled to me. “I recognized your cry from below the impediment! I longed to find you! There is no treasure in this settlement that could match in magnitude the joy I obtain now when I touch the skin of our deliverer! May I give my thanks to you!”

Her emotions swirled through my head, down my neck, before finally settling in my abdomen, so parched, so empty, so long crying out for nourishment, and now satiated by a mixture of soothing passion, whose ebullitions rose to my throat and filled my eyes with tears.

“Sister,” I shrilled, as I gently pushed her back, “allow me to detain you no further. May you express your gratitude toward me by allowing me to see you feast upon my deliverance. Go, sister! This is yours! I give this to you!” She gave an incomprehensible squeak of delight before turning away and disappearing into the crowd.

When she had left, I nearly collapsed as my physical weakness overtook me once again. My bodily starvation, though rejuvenated to an extent with her potent gratitude, began to creep back to me.

I had been unable to hunt freely—for ponies did not hunt but rather waited to be served by others. It had been aggravating, having to depend on them for my food and having to wait when I had been ravenous. In addition, they were herbivores, so the only meat I had been able to get was from the abominably-tasting pigeons of the city, whom I could hunt only rarely at the risk of being discovered as an interloper, since hunting the ponies themselves had been out of the question then.

And that accounts only for the hunger of the body. My family is afflicted by a double-pronged hunger, one of the body and one of the soul. And what solace is there after the body has been filled if the soul remains black? Love, affection, fear, apprehension—we crave all these things. My sister queen had had her fill during the past months, for the unwitting captain had loved her as if she were his very mate. But what about me? How had I gotten these things before now? In agonizingly small doses: a smile whenever I’d held open a door, a warm thank you after picking up something dropped, a firm hoofshake from the sentry after giving him a summary lecture in a certain aspect of morphology. But how few and far between! How fleeting the solace is!

To have to worry about these two stomachs, to ingratiate by day and kill by night, to be forced to rein the teeth-grinding madness of hunger lest you and your family be discovered, to have that hunger never satisfied, to not know if it’ll ever be satisfied—these are the torments I’d endured, and survived, in the past months. These are the torments from which I’d extricated myself and my family.

I ducked off into a dark alley that my brothers and sisters had not seen in their haste. It turned off onto a street that led to a quiet, neighborhood-like area, easy to miss by those unfamiliar with the city.

I came out onto a small residential square. It was tranquil, as it usually was, but the silence that now prevailed was not the peaceful one I had known it to have; rather, it felt like the horrified silence of a petrified animal on the verge of emitting a despairing scream. And the knowledge that it was due to us that this once peaceful atmosphere was now permanently altered brought no small amount of pleasure to me.

There were one or two ponies standing on the street with their ears perked up, listening with fatuous and indolent attention to the growing rumble of a force which they would eventually wish they had not stopped to hear. I saw only the tails of a few others, more prudent of the kind, perhaps, disappear behind the doors of various apartments and stores. I caught the worried stares of a few ponies from the windows across the street, and when they saw me, their eyes assumed a stare of abject terror when they saw mine relax into a repose of sublimity. They then pulled their faces out of sight as fast as they could, and the blinds dropped over the now-empty windows with a violence that would not have been matched had they simply fallen straight from their metal holders.

On the corner of the street, I spotted a smaller, brightly-lit store over whose threshold was stenciled on a wide board in bold, red letters, the word CONVENIENCE.

I remembered this one; it was the first store that I had had the nerve to enter when I had first come to the city, and it was the establishment that had seen my first use of the ponies’ bartering system. It was a small business; its sole proprietor operated the store during all its hours, and I assumed that the blur of color that I could see, darting between the ranks of the shelves with a frenzied intent, was he.

I watched him for a while as he erratically scurried back and forth between his little stocks of food—a response that I had thought an option only to the lowest of insects. But, unfortunately for him, despite the fact that that defense maneuver had been used ever since the first ant had appeared on the earth, it had never stopped the torrent of water from destroying with impunity its wretched hill of sand.

The door was locked; but such a crude mechanism, I had learned, only really kept out those who weren’t determined to come in in the first place. It was easy to destroy. I gave a firm kick to the door, and a very satisfying crack resounded through the air as wood and plaster splintered.

I sensed three bodies on the shop’s floor. The first was the one I had seen from outside, the shopkeeper. He was a stout, yellow thing, with circular glasses and a brown mane. He was not wearing that constant, pointless smile that I remembered, and his silence at that moment hid his stutter. I also remembered that he had spoken to me and that it had been almost impossible to comprehend his meaning. But that speech impediment—for a reason which I will never understand—seemed to charm his patronizers.

It was an odd sight, seeing him standing there, looking with an uncharacteristic stare of damnation upon me, as if I were someone whom he had never seen before in his life, nor had ever talked to. In his mouth, he clutched the long wooden handle of a sledgehammer.

I heard a whimper in the direction of the freezers. I looked: There was an adult female of the unicorn variety, a light shade of red, almost pink, with a bright yellow mane. She was lying on the floor, curled in on herself. The skin on her back shuddered with every breath she took. When she saw me, she slammed her eyes shut, and buried her head into a fleshy green mass which she was trying to cover from sight with her hooves. I looked closer, and I saw the third entity. The unicorn was holding a smaller pony, a green one, at whom I didn’t get a satisfactory look, and the length of the adult’s foreleg was covered over the juvenile’s eyes, preventing it from looking in my direction.

I knew these two. They lived in the apartments above the store. The unicorn and the juvenile were the proprietor’s mate and offspring respectively.

I looked back to the owner. He was looking over to the two in the corner. When he noticed the fast twisting of my head, he turned his gaze back to me. This time, I noted with interest how his countenance had completely changed from that of earlier. His brow was no longer furrowed in the hostile response, but rather raised as an animal raises its brow when expressing a desire for pity from a superior. He let his face and posture sag and let the hammer droop a little from his mouth, just enough for him to be able to utter the raspy word: “Please.”

I stood up straighter and took to my wings, hovering a few feet in the air. Performing the universal gesture of the remonstrance of a natural opponent, I looked down on him and bared my teeth. “The presence of others in your dominion changes nothing,” I shrilled. “You have sustenance; I and my brothers and sisters need that sustenance. It can be taken through your cooperation or through our force. In either case, this is now ours. If you choose the latter option, know that our actions will not relent until you have entirely capitulated.”

He probably didn’t hear my words, and if he did, he heard them only as a few quiet clicks and buzzes. But that didn’t matter, for the words did not matter in themselves; only their intent did. And the threat of violence is a notion that is innate in all species and understood by all of them. When I had finished my speech, he took a step back, and I knew he was pondering the decision.

Then, in an instant, the dangling hammer snapped taut in his mouth, and he assumed the stance he had been in when I had first entered. He, too, bared his teeth, and he made a growling noise from his throat which did not form the sounds of any of the words of their language—but, taking after my lead, he, too, was speaking the universal language of pure intent.

His teeth were grasping the physical middle of the handle; and, for a second, I hesitated. To hold it completely horizontally at that position and to stand unflinchingly straight required a remarkable amount of force exerted by his teeth alone.

But then I remembered: The structure of ponies’ teeth was fearsomely strong—but the cutting parts were blunt. I laughed as I tongued my canines. Yes, their teeth were blunt—pitifully, cripplingly blunt.

An eloquently narrated prologue with a superb vocabulary. I have a lot of confidence in the future of this series

Just reading this makes me feel like wearing a mustache

Superb style of writing almost and wonderful minor cliff hanger at the end here.

This is interesting. Your write your anti-hero in a way that's not evil.

3750892 if he's not evil, he's certainly callous. To disregard the life and liberty of entire settlement, one in which he lived for a significant amount of time, and by his own admission, was treated kindly and fairly by?

That's a pretty dick move. Changelings feed on Empathy, but they, or this one at least, certainly lack it.

A long adventure fic, with changelings, and it's about linguistics? Count me in!

It's impressively well-written, too. Errenax is a chilling villain, evil and ruthless but in an intellectual way. His calm, observational tone almost reminds me of George Orwell at times – except where Orwell wrote against power-worship and violent domination, Errenax is all for it. It's a bit like reading Nineteen Eighty-Four from O'Brien's perspective. I'll definitely be continuing this.

Two passages jumped out at me:

"Ironicalness" is an awful, nails-on-chalkboard word. It's convoluted, it's clunky, it's ugly. Why not just use "irony"?

Then again, the fact that this stood out so much speaks to the otherwise excellent quality of writing in this prologue.

Anything that can eat city pigeons and live has an insane immune system. My respect for the changelings grows.

this is a very original concept!

it is dense, though i suppose it has to be given what you are trying to do with it.

some chapters feel a bit like reading a technical paper. it is a little over my head! but i like it which is kinda the bottom line i guess?

you know a lot about this stuff!

Bozhe moi!

That certainly sounds ominous...

It certainly is unfortunate that Errenax did not discover the vocations of marriage counsellor, lifeguard, or ice cream vendor. He could have been fat, happy and satiated by now...

As many have said before, this certainly is an exciting start. I am certainly looking forward to reading this.

Just out of curiosity, do you (the author) have and formal training/education/work related experience in linguistics? This story reads like it has been translated into English/Equestrian from an altogether different language with different syntax, grammar, structure, and moods (which I suppose is completely the point).

This is great writing. Sorry I didn't read any of your stories until now. I hardly ever read longfics.

Very interested to see where you go with this idea of concrete vs. subjunctive. The usual divide in human culture is between concrete empiricism and abstract idealism.

(Nitpick: The idea that the verb "to be" takes a nominative object is a myth. No one has ever spoken English that way except under the influence of bad 19th-century grammarians who wanted to make English more like Latin. Can you say "It's I"? No, you cannot. The exception is relative clauses: "It is he who hath made us" is correct to the extent that "he who hath made us" is the object of "is".)

Nicely done. The alienated grammar itself, as in, its influencing the story-telling aside, taking only its pure beautifulness into consideration, is enough to stand this work out.