Well Excuse Me, Queen! · 9:33am Oct 7th, 2013

Fantasy stories and animated shows that contain princess(es) often has one thing that bugs (no visual pun intended) people to no end, to the extent that it inspires lengthy academic analyses: Princess being the apparent, uncontested ruler of a kingdom, yet are not titled queen. This issue has been tackled in multiple angles, ranging from how the big culture we are in enables such characterization, to how the often-intended audience, young girls, personally view those labels, to simple artistic merits, etc. It is indeed an amusing and yet thought-provoking topic.

Here, I want to look at it using a slightly different approach, by examining the historical roots of these royal terms and, hopefully, provide a coherent context for this kind of curious terminological discrepancy.

So first we have king and kingdom. Kingdom, ruled by a king, or his female equivalent, a queen. Sounds only natural, right?

The English word king comes from Old English cyning, cognate to words for “king” in other Germanic languages such as German könig, Danish konge and Dutch koning. In Beowulf we have this sentence which repeated three times throughout the story, with each use increasing in irony with reference to different kings (Scyld, Hrothgar and Beowulf):

Þæt wæs god cyning!

That was [a] good king!

The Old English word cyning can be broken down to cyn- and -ing. Cyn(n) is related to modern English kin, both of which mean “kin, kind, tribe, people”. -ing was a common patronymic occurrence in Old English names, meaning “son of, originating from”. A king therefore originally denote a “son of the people”, not a towering father-figure of the tribe, but is one with the tribe, a representative of the whole tribe “who symbolizes peace, order and harmony” (See Leo Carruthers, Kingship and Heroism in Beowulf, p.19).

-dom is an abstract suffix that, among its whole slew of meanings, can signify “rule, power, glory, majesty, state, or condition”. The combined form cynedom or cyningdom was well attested in Old English literature, both of which, from the above etymology, mean “rule of people’s representative”. It is important to note that in Anglo-Saxon traditions, kings were elected from the people, their power was duty-bound and ultimately derived from mandate of the people; the later medieval concepts of divine rights from born and kings being the absolute apex of the society, while more well-known and readily perceived by us, were not dominant back then.

Queen comes from Old English cwen, which roots in Proto-Germanic (*kwoeniz) means wife or woman. The sense as in “female consort” was a derivation in Old English, with that as in “female ruler” an even later development. Indeed, there was no female equivalent of princess or earl in Old English. Before the Anglo-Norman term princess entered English, cwen was also used in addresses towards royal princesses, or any other highborn females.

Princess is the feminine form of prince in Old French. In French they carry the meanings of “those of noble/royal birth, ruler or consort”. When the term was borrowed into English in 14th century, it first denoted two things; one was the same as it is commonly understood now: female members of a royal family other than the queen, especially the direct descendants of the king or queen regnant. The other meaning was to refer to those who excel in a given class or field, curiously mirroring the modern street use of the word. A century later, the word came to be associated with other derived meanings, such as the female ruler of a principality or other small states, especially those who were subordinate to an emperor or a king. Of our interest, princess was indeed used to refer to a female monarch or ruler, albeit just intermittently and becoming an archaism over time.

For example, in Edmund Spenser’s epic poem The Faerie Queene(1590) we have the following prose:

And running all with greedie ioyfulnesse

To faire Irena, at her feet did fall,

And her adored with due humblenesse,

As their true Liege and Princesse naturall [...]

Princesse, in this case, naturally referred to the Queen Irena.

Also, Philip Stubbs, a vigorous Puritan pamphleteer, provided us with the following quote in his best-known work, The Anatomie of Abuses(1583)1:

To the accomplishmente wheros God graunte that those holsome laws, sanctions, and statuts, which, by our most gracious and serene princesse (whome Jesus preserve for ever) and her noble and renowmed progenitors, have beene promulgate and enacted hertofore, may be put in execution.

This princesse here was of course the “Good Queen Bess”, Elizabeth I of England, also known as the Virgin Queen.

So we do have historical precedent to call a queen regnant of a kingdom “princess”. Looking further, prince and princesse came from Latin Princeps, derived from the Roman Emperor being first among equals in the Senate (Princeps Senatus). The title princeps in Roman times is an indication, or at least a pretense, that the ruler drew its rightful power to rule by virtue of being the first member of precedence in the Roman Senate. Later emperors would discontinue the use of princeps and adopt the title dominus “lord”, thereby dropping the pretense altogether. But at least we can see that the titles prince and princess, even if strongly associated with monarchy and royalty nowadays, did have a historical root based in the ideals of democracy and equality.

Of the two potential terms for a female monarch, if you disregard the modern connotations brought on by years of Disney indoctrination, their roots do not entail much comparative advantage over each other when you want to apply one of them to the image of a benevolent, minimally despotic monarch. There is nothing wrong to use the title “queen”, it plainly denotes “female ruler of a kingdom”. Its humble etymological origins and its historical use to refer to female high-borns other than the queen regnant are also plusses. On the other hand, we do already have some cases of historical uses of referring to queens as “princesses”, and that the title’s ultimate connection to egalitarian ideals is also attractive. As for “kingdom”, we have certainly displayed some flexibility in our language use already, seeing how we do not call a kingdom a “queendom” instead during the reign of a female ruler, plus if we are allowed to invoke the original root components of the word: so long as the ruler is considered by the people as their true representative and leader, this term for the polity could already hold, if not arguably.

To the end, the relationship of a particular lexeme, or word, to a certain meaning must have begun with arbitrariness. So it may be a reason to calm ourselves over the almost compulsive urge to rectify perceived disuniformity in languages. However, we should also acknowledge that humans are born with a penchant to patterns and regularity, and it is unlikely that people will get over the uneasy feeling whenever they see a kingdom without a king or a queen any time soon.

Also, this is not to say the modern popular conception of princesses and queens do not give us materials well worth analyzing, for example, in terms of perception of youth and beauty, rights and personal responsibility, etc. For one, the Nostalgia Critic has made an entertaining editorial on this matter, which is quite worth watching.

So my position at the end, is to continue to suspend disbelief with regards to the story setting, give the benefit of the doubt to the creators using a convenient in-universe justification (or inconvenient justifications like the mouthful above), but keep the mind open to ponder the extra-fictional reasons why the creators choose to do so.

By the way, do you know that crispens (“to make crispy”) is an anagram of princess?

P.S.: I know in the Zelda cartoon there is indeed still a king around, the title is simply a play on the oft-used meme.

1 He would later use his wife as an example for a paragon of virtue. On her deathbed, she declared that her affection towards her puppy was but a sinful vanity. It is hard to not liken him to some modern fundie bloggers.

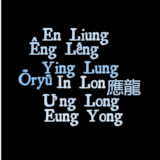

Image courtesy of ShadyHorseman

Princess it is! (I knew it had something to do with "first"!)

Actually, because of Prince Blueblood, I've been of the opinion that Prince/Princess is simply the only noble title left, much like Emir in the UAE. All the lower ranks got promoted, all the higher ranks (if any existed) demoted; if you're a noble, your a prince/ss. This would also explain why Twilight was not already the Marchioness of Ponyville and Everfree. (Countess would have been an acceptable form of address )

)

1402291 I think the exact nature of noble titles to that of an Equestrian feudal system, if any, is left quite open in the canon. It certainly has some stylistic trappings though, for example, does the existence of castles implicate medieval-styled warfare or defense? Also, names like Shining Armor hints at the existence of knights (lowest noble rank?). Rainbow Dash even explicitly called Fluttershy "Knight Fluttershy" when she went jousting.

The uses of the term lady, while can be understood as a polite address, can too be construed, at least in some cases, as referring to females of royal or noble status. Historically in Britain and Ireland, lady is the successor of cwen in Middle English to be used in personal addresses to those highborn females. So while leveling of titles is an attractive and parsimonious proposal, I would remain open to the possibility for the existence of other noble ranks. It is also less likely to be jossed by the creators this way, eh?

1402320 It's certainly quite open; it's not like Twilight called the rank of Countess 'defunct' or anything. I just think it unlikely that the Diarchss title would be used by anypony else if there were any extant titles available.

It's entirely possible that knight is another defunct title, just one that was used until a more recent time, and thus better remembered. (It's also a title more likely to come up in fiction, as knights are know for what they do as opposed to how they are born). After all, Knight Fluttershy (and not Dame Fluttershy, as it would be if we were using the British Norman system) is part of a historical re-enactment. Historical, that is, from the perspective of ponies who have been frozen for a thousand years.

Shining Armor may reference the chivalric* ideal, but that doesn't require the system that created the ideal to still be in place.

* we need to look into that word. It's original meaning, if I recall correctly, referred to "taking care of horses."

1402389 Chivalry is now understood as the qualities of being a knight. This sense was derived from its original meaning of "knighthood, a body or formation of knights" from 13th century Old French chevalerie, chevaler being a knight or a horseman in an army.

Chevaler and cavalier both ultimately descended from Vulgar Latin caballus, which in Classical Latin means "pony, nag, pack-horse" and displaced the Classical Latin term equus "horse".

Speaking of which, the etymological root of Equestria - equester - exactly means knight in Latin. Caballaria would be a Medieval Latin equivalent of Equestria.

But of course, I'm just making speculations for fun; I don't really swing strongly towards any way with regards to headcanons/fanons. I would be content with a good entertaining story either way, as long as there is a coherent setting and gripping plot.