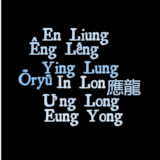

Yinglong Fujun’s Linguistic Corner 3 – History as Seen from Toponyms, Part 1 · 1:54pm Sep 9th, 2013

Toponym is a Greek-derived word meaning ‘place name’. From studying toponyms, scholars may learn a lot about the ethnic distribution and migration pattern of the past, especially in times when written records were scarce. In the world of fiction, stories with meticulous world-building process usually have at least some attention and effort put into the naming of geographical features; the Middle Earth as described by J.R.R Tolkien may be the most illustrating example of such importance. A carefully constructed world which gets even the smallest details polished, like place names, gives off a sense of seamless complement, immersion and most importantly, a heavy sense of the years past. Bottom line, nothing is more jarring when you realize the Clearwater River runs through a mountain named Belthusalanthalus.

So you may ask, ‘what do all of these have to do with MLP?’ Well, I would like to study place names with liberal use of guesswork as well as some generous linguistic assumptions1, to see into some unintended implications on the past history of Equestria from the toponyms.

Well, I may have previously complained about the cheesy puns ubiquitous everywhere in the setting, but within the fourth wall, inserting names of species and body parts may be an idiosyncratic cultural practice.

I would further suggest a possibility that this kind of punning, when considered in-universe, signify the ponies’ foreignness to the land now called Equestria. As we have explored back in LingCorn 1, place names are usually meaningful in their native tongue, at least initially, before displacement of populations and linguistic evolution brought about by time. In the former case, when a new group of people, speaking another tongue, arrive at one place where its old habitants have left or dwindled in number, they may adopt, or more precisely, assimilate the old name in their own tongue – the meaningfulness would be lost in this process. Of course, changes in spelling, pronunciation and the status of referent over time would also do that to a toponym even when the original speaking community has not been displaced.

Consider the English toponym, Bredon Hill. It is an interesting case of tautology as bre, don and hill all mean the same thing: hill, so really the whole word literally means “Hill-hill hill”. How did this come to be? Well, Bre- is Celtic (or more precisely Old/Early Modern Welsh), and that was just how the local Celtic people call that elevated plot of land – a hill. When the Anglo-Saxons came along, since they clearly couldn’t understand the Celtic tongue or what “bre” was, they presumably thought “Bre” was some sort of proper noun and affixed a “don” (hill in Old English) behind denoting, “yes, it is a hill”. Hundreds of year later, the word “don” became obsolete and was no longer used to denote what we now call a “hill”, so people add another “hill” to the end of the toponym, referring to the same geographical feature as were described by their ancestors.

Another yet more illustrating example of how foreign peoples misunderstand and assimilate, in a way akin to mondegreening, native toponyms, is the many names of York. Originally named Eboracum, “Place of the Yew Trees”, under the Romans who adapted the native Celtic name, it was re-interpreted by the Angles who moved in as Eoforwīc, “Wild-boar town”. Later, when the Vikings took over, it again became Jórvík, “Wild-boar creek”; note how half of it (Jór) was adaptation2 and another half of it (vík) was a reinterpretation. And over the years, Jórvík simplified and become the name we all now know, York.

As a good number of Equestrian toponyms are simply North American toponyms with puns, we may assume that similar reinterpretations by folk etymology happened when ponies moved into the land mass we now called Equestria. The puns may themselves be a testament to both the reinterpretation process and the tendency to use body parts or self-identification while doing so. As we see, the components of a number of Equestrian toponyms are interpretable in English e.g. Hoofington, “Town of Hoof’s people(ponies?)” but some of them are of apparent “foreign” origins, like Manehattan and Appleloosa, which real-life referents do have non-European etymologies. We can logically treat the punning practice as the way how ponies assimilate native (Buffalonian?) toponyms which may sound like "hoof" or "mane" to pony ears but in truth may mean something else entirely. Pony puns can therefore be partly seen as a linguistic-cultural artifact of their past migrational history.

Afterword: Consider the parallelism to America established above and in many other aspects of the show, including that from the show, we know inhabitants other than ponies e.g. Buffalos do live off the land of Equestria, albeit in a state of competing for lands… So is it possible that Equestria like America in real life, foreign pony settlers encroached on and chased off the original inhabitants off their land? (Gasp) Is the Windigo story simply some sort of justification for Pony Manifest Destiny? I have no clue, but the other fact that ponies seem to be the dominant species and live on the lushest, most fertile land on Equestria is making me suspicious. Yep.

Also, I am still thinking about the materials to be used in Part 2, it would eventually come along some time...

1 One of them is to treat the Equestrian language as a form of "parallel" English; also, any change in different linguistic aspects should be caused by a corresponding portfolio of factors as in real life. This assumption can be seen as irrational depending on how stringent you want to the criteria be; after all, a pony typewriter only has two buttons, how can one make such bold assumptions like these about the nature of their language? But then again, it is hard for us to consider ‘otherwise’ (What exactly would they be speaking if they are not speaking English? If so, how can we plausibly explain all the language quirks that only make sense if they speak American English?) In any case, this little exercise should be strictly treated as a form of ‘what-if’ experiment, a ‘fan theory’ if you will.

2 Viable because Old English and Old Norse are both Germanic languages. They sometimes contain easily adaptable cognates, but some occasional false friends too.

As for footnote 1: I actually like the concept of Equestrian as an English analog, because English is a language of many parents. It's considere Germanic, but it's really a cross between Saxon (Germanic, central/west) and French (Romance, with heavy Frankish (Germanic west) influence) So English is about as Romance as you can be while still being called Germanic, and French is right acroos the line. But the vocabulary of English (notoriously) borrows from a large number of other foreign tongues; most notably Latin, Greek, and Aborigional languages.

Old Earth Pony: German

Old Pegasus: Greek

Old Unicorn: Latin

and Buffalo dialects in place names and wildlife names.