Mythologia 2 – The Pegasus Puzzle · 8:46pm Sep 30th, 2016

Link to Mythologia 1 – The Unicorn Question

Preface: It is almost three years since my last post on unicorns. I figure that a new piece of writing on mythology related to Equestrian species is long, long overdue. After all, some of my readers may have subscribed and paid heed to this blog and user because of non-fictional reference posts, and it does not sit right to me to inundate these readers with my story ramblings.

Though I am no literature, history or anthropology major, I have armed myself with my literature research skills as someone trained in social science to tackle the next major species in lore – the Pegasi. Admittedly, I was stumped by a lack of suitable references (that I could find), and it forced me to put this project on hold (for how long!). However, now that I have accessed to inter-university resources again, I can finally write up a post with passable quality.

This blog post will go wider in scope than the unicorn post, and it would be broken down into multiple parts, because I would delve more into the parallels and derivations of pegasi around the world, which are highly intriguing in their own right.

Contents

The Advent of Winged Beasts

The Greco-Roman Pegasus

The Norse Pegasus

The Asian Pegasus

The European Pegasus

The Modern Pegasus

The Advent of Winged Beasts

When in history did humans first conceive the sight of a winged horse dashing through the sky? Even though it would be hard to pinpoint a concrete year, we can fairly certain that the first rendition of winged horses was born in the Ancient Near East, the crucible of chimeric yet sacred animals.

The Sumerians in Mesopotamia and Elamites in Iran described a lion-bird hybrid, creatures with lion head and eagle wings (A ‘reverse’ griffin, so to speak. Griffins will be expounded on separately in a future Mythologia post).

Ancient Egyptians, who had extensive cultural contact with the Greeks, were famous for the sphinxes – winged lions with human face – object of solar worship as well as dedication towards the sun god Atem.

The Lumasi (singular: Lamassu), oxen with bird wings and human face, was a protective deity of ancient Assyria. They were often placed at the entrance to houses and cities as a ward against evil.

The combination of animals perceived as wise, fierce and elegant gave rise to a caste of ultimate animals, they were divine, powerful and above mortal matters – eminently suitable to represent the absolute sovereignty of ancient rulers.

It should be noted that even though the Greeks were the progenitor of the modern concept of pegasus in the west, winged horses might be described and depicted in elsewhere before.

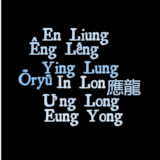

For instance, the red-iron clay stamp above (collection of the Middle Eastern Culture Center in Japan) was unearthed in Syria. Ladybug-shaped stamps were prevalent in Syria and Palestine since 1500 BC. The resulting seal on the amulet showed a galloping horse with a primitive, branch-like wing atop. This way to represent wings was a Mesopotamian tradition that could be dated back to the third millennia BC. Nonetheless, the most recent bound of the dating lies within the Achaemenid period (6th to 3rd century BC), making it impossible to discount the possibility of later Greek influence.

The Greco-Roman Pegasus

The Greek origin of pegasus was definite and influential. The word Pegasus is derived from Greek Πήγασος (Pegasos), imported into English in the 14th century via Latin texts on Greek mythology. European imagination of pegasi most likely began with the systematic consolidation of Greek mythology in the hands of ancient Greek poets.

Traditional understanding points the genesis of the term pegasos to springs (πηγή, pēgē). It was said that wherever Pegasus set his hoof on, a spring would well up from the ground, and in these fountains, pools, brooks and wells will give rise to water nymphs called Πήγασιδες (Pegasides, begotten of Pegasus).

You might notice that the term ‘Pegasus’ in Greek mythology does not refer to a race of winged horses. Pegasus is a singular character, the personal war-steed and bringer of thunder for the mighty Zeus.

The earliest surviving Greek text about Pegasus is from the Θεογονία (Theogonia, Genealogy of the Birth of Gods) by ancient Greek poet Hesiod. Hesiod lived in an age whereby the afterquake of the Mycenaean collapse and the subsequent Greek Dark Age had finally passed, and the classical poleis (city-states) of Greece were emerging. It was against this background Hesiod composed Theogonia, which synthesized the disparate local traditions across Greece and associated polities in Anatolia.

Marble Bust of Hesiod

A likely origin for Hesiod’s pegasus is curiously non-Greek. Luwians, neighbors of Hittites who had lived in the region of modern-day southwestern Anatolia, worshipped a god of weather and lightning named Pihaššašši. Not only are Pegasos and Pihaššašši likely linked in etymology, the role in their respective mythology – thunder-bearers – also suggested an occurrence of cultural osmosis (Hutter, 1995). (Note: This also makes the weather-making ability of pegasi quite true to the source.) An educated hypothesis would be that Pihaššašši was adopted by the archaic Greeks, who reimagined and put it into the Greek bestiary as a mythical steed subservient to the chief of the classical Greek pantheon.

Geographical distribution of Luwians

Many versions of the myth concern the birth of Pegasus. The earliest extant version, the one written by Hesiod, pinned his father as Poseidon the God of the Sea, and mother as Medusa the Gorgon. And as with many tales in Greek mythology, I would use the concept of parentage rather loosely. This is because Pegasus was said to be born from a mix of white ‘sea foam’ (ahem) and Medusa’s blood from her beheading by the hero Perseus. Poseidon was no stranger to equine creation. Indeed, he was said to be the creator of the first horses, beautiful animals used to impress Demeter the goddess of harvest. In another version though, Pegasus was simply born from Medusa’s spilled blood on the ground. After he was born, he ‘came to the deathless gods (Olympians): and he dwells in the house of Zeus and brings to wise Zeus the thunder and lightning.’ (Hesiod, Theogonia, 270).

Birth of Pegasus by Edward Burne-Jones

The most famous of Pegasus’s exploits concerns his relations with the hero Bellerophon, a monster-slayer before Heracles. His greatest claim to fame was spearing Chimera, a creature begotten by Typhon, son of Gaia and Tartarus, and Echidna the she-viper, with “the fore part of a lion, the tail of a dragon, and its third head, the middle one, was that of a goat, through which it belched fire” (Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, 2.3).

Bellerophon got his name from slaying a tyrant called Bellerus in Corinth. He, however, also committed the sin of fratricide, and had to go to Proteus, the King of Argos and Tiryns, to be purified. The consort of Proteus, Stheneboea, took fancy on Bellerophon. But when she was rejected, she falsely accused Bellerophon of sending her a ‘vicious proposal’. Proteus believed her, and suggested to kill Bellerophon in his correspondence to Iobates, Stheneboea’s father and King in Lycia. Chimera was to be the borrowed sword for Iobates to kill Bellerophon with. However, Bellerophon successfully defeated Chimera instead.

Pegasus was the winged steed Bellerophon rode on to battle with Chimera. He flew from a height, soared down and struck the Chimera down in a dash. This would be the first of Bellerophon’s many heroic deeds.

Other authors expanded upon the conditions in which Bellerophon found and acquired the service of the divine steed. For example, Pindar (c. 522 – c. 443 BC) stated that Bellerophon tried desperately without success to harness Pegasus in the city of Peirene, until the maiden Pallas (an epithet for the goddess Athena) brought him a golden bridle to tame the horse with, while the latter was drinking from a spring (Pindar, Olympian, 13).

Taming of Pegasus by Jacques Lipchitz

However, after all the adventures, Bellerophon grew proud and wanted to ascend to the dwelling place of the Olympians on the back of Pegasus. As such, the disgruntled steed threw Bellerophon off on his way to the heaven (Pindar, Isthmian Odes, 7).

Afterwards, Pegasus continued to serve under Zeus as his faithful companion in Olympus, as a bearer of his thunderbolts. Aratus Solensis (c. 315 BC/310 BC – 240 BC) related in his work Φαινόμενα (Phaenomena, 206) that Pegasus, being mortal, was eventually rewarded with catesterism (divine uplifting into the stars) by Zeus, becoming the constellation of Pegasus.

Curiously, the famous Homer might have seen the Pegasus as an unreliable addition to the heroics of Bellerophon, for he neglected to mention the steed by name, and only stated that he rode forth in the “blameless escort of the gods” (Homer, Iliad, 6.179).

Winged horses in Greek mythology, though, were not limited to the most famous example. Winged horses other than Pegasus did exist in the mythical Greek world, chiefly as chariot-pullers of the gods. For instance, Pindar described how Pelops, King of Pisa in the Peloponnese, begged Poseidon for a swift chariot, and indeed he received a golden chariot pulled by horses ‘with untiring wings’ (Pindar, Olympian, 1).

Pegasus might also have winged horse companions, albeit unnamed, together in service to Zeus. In Bibliotheca, an epitome of Greek heroic myths, Pseudo-Apollodorus (‘Pseudo’ because Apollodorus of Athens was unlikely to be the true author), there was an epic battle between gods. Typhon (again) challenged Zeus for the rule of Cosmos. Zeus kept throwing thunderbolts at Typhon at a distance, but the monstrous giant still managed to sever the thunder-god’s sinews and hid them somewhere. After Hermes and Aegipan recovered and fit the sinews back to Zeus’s arms and legs, Zeus rose again from the heaven, and this time his chariot was pulled by a multitude of winged horses (Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca, 1.6).

Zeus battling Typhon

Even Plato used winged horses in his philosophical texts as metaphors, likening the human soul as a duality like winged horses and their charioteers (Plato, Phaedrus, 246a). We can see that while Pegasus in antiquity might have referred to a specific steed, winged horses as a motif were prevalent in ancient Greek discourse.

The Romans would inherit the Greek traditions into their own telling of classical myths, and continue to employ the iconic winged horse in their art, using Pegasus as a symbol for immortality.

The Italic tribes were indeed no strangers to winged horse motifs. Indeed, one of the pinnacles of Etruscan art is a pair of winged horses found in Tarquinia (see above). The Greek connection was undeniable – the style of the terracotta panel closely resembled Greek sculpture of the same era. The winged steeds guarded the Altar of the Queen, and were originally decorated with vivid colours.

The Romans themselves also adorned their painted vessels, bronze mirrors and other personal affects with the heroic images of Pegasus and other heavenly horses. Pegasus and other winged horses, by then, had become a veritable member of the Roman folk religion.

The Norse Pegasus

While the word Pegasus was of undeniably Greek origins, the fascination with flying horses in European traditions likely also came from another source – the Norse mythology.

Ride of the Valkyries

Valkyries bringing worthy souls into the halls of Valhalla is one of the most iconic imageries of Norse mythology. Horses were the steeds of choice for Valkyries, as they rode down from the Bifröst (rainbow bridge) of Asgard, in order to select half of those who perished in a bravely fought battle and bring them into heavenly blessing.

Still, one big question is that whether the sky-dashing steeds described in the sagas really had flapping wings like pegasus. Although in Old Norse work the flying horses are seldom explicitly said to possess wings, one promising candidate would be Hófvarpnir (Hoof-thrower), the gliding and swimming steed of the goddess Gná. Gná was the messenger of Frigg, the wife of Odin.

Gná and Hófvarpnir (right) in front of Frigg

Jacob Grimm, in his treatise Teutonic Mythology, suggested that even though Gná herself was explicitly said to be unable to actively fly (Snorri Sturlusson, Prose Edda, Gylfaginning, 35), Hófvarpnir might possess wings similar to Pegasus (Grimm, 897).

Speaking of which, the day-bringing horse Skimfaxi (Shining mane) and the night-bringing horse Hrímfaxi (‘Rim’ mane, or frost mane) flew in the air, pulling the sun and the moon across the sky respectively. However, they are not specifically said to have wings, and winged depictions are uncommon. Nonetheless, horses or horse-drawn carriages that performed the duty of pulling celestial bodies are a recurring theme in Indo-European mythology in general.

Curiously, Grimm also mentioned a difficult issue when we are to determine whether Norse horses are winged. This is because in Old Norse, all high-flying things are said to ‘gnæfa’ (to fly, to flow, to trot or to creep). It is relatively unclear that whether creatures with the ability to stay actively airborne are wingless but flying, or that the author saw no need to stress that flying creatures naturally possessed wings.

It is, though, not a far-fetched notion to presume at least some of these divine steeds had wings, since birds, who supplied the fascination for flying before human flight, have been a staying mythic symbol of divine messengers. Ravens are the chosen messengers and scouts of Odin, and in various European cultures, they are the birds that go on errands, bring with them intelligence and tidings of the world. Still, it was not until late Romantic to modern era that winged Norse steeds became more depicted in artistic works.

The Asian Pegasus

To the East of Greece, the home of Pegasus, the heavenly horses also flew towards the Orient. When Alexander the Great conquered the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, Greek influence rapidly spread eastward into Asia Minor, Mesopotamia, Persia, even India and the Steppes. The winged horse imagery became embedded into local Zoroastrian tradition, and became more widespread than ever. In a sense, the motif of Pegasus, since its birth, went in the opposite direction geographically compared to the unicorns.

At the meantime, the steppe-roaming peoples in Central Asia began to depict winged horses – the Tulpar – as their divine steed of devotion. The wings, though not necessarily a sign of flight, were nonetheless a surefire sign of speed. It was relatively unclear whether it was an independent development or an influence from distant Greek traditions. It was not difficult, however, to imagine that the steppe people, who lived in a close relationship with horses during hunts, and also used birds of prey to locate their targets, would go the natural route and synthesize the two most intimate animal companions together as a divine symbol of swiftness and power.

Tulpar on the Emblem of Kazakhstan

In Islam, Haizum is said to be the personal steed of Archangel Jibril (Gabriel). He is a white flaming winged horse that could transcend cosmic planes. Related was the steed Buraq (Lightning), sometimes depicted with a humanoid face. He was a tall, white steed that carried Prophet Muhammad to the farthest mosque, and then to the many heavens at night.

Persian representation of Buraq with humanoid face

The imagery of winged horses also arose in China. Tianma (Heavenly horses) motifs could be dated as early as the Western Han dynasty (3rd – 1st century BC). They were said to be divine creatures that roamed the Immortal Lands, where gods and immortal spirits resided. Tianma were closely tied with ancient Chinese folk religions, as they could be observed in burial sites as relics.

Copper statue of Tianma

A related steed is the Qianlima, or the Thousand-Li Horse. Qianlima is an excessively swift winged horse who is said to be able to gallop a thousand li (about 400 km or 250 miles) per day. It is also a noble and elegant steed that would refuse any mortal who dares to mount him.

Chollima (Korean Qianlima) of the ancient Kingdom of Silla

Longma (Dragon horse) was a winged horse with dragon scales, and it had an even more ancient mythological past. It was said to be the divine steed that bore the River Map (an ancient Chinese magic square) and gave it to Fuxi, the co-progenitor of humans, who then used the Map to create the trigrams and the famous divination text I Ching. The modern Chinese idiom Longma Jingshen (Longma Spirit) is a phrase of blessing for good health and spirits, and directly references the propitious beast of myth.

The winged horse motif would be further strengthened by interaction with distant Western influences. By the time of Tang dynasty (c. 6th - 9th century), winged horses were widespread as an auspicious symbol. Bronze mirrors, textiles and crafts bearing winged horses were not only made in China, but also imported from the West via Silk Road. Artefacts bearing the likeness of pegasi could be found as far east as Japan.

The Medieval Pegasus

The dignified tales of Pegasus and divine winged steeds would later give rise to the medieval European impression of pegasi being a symbol of fame, of wisdom, of tenacity, and of integrity.

Understanding of Greco-Roman mythology remained a privilege of the learned caste in medieval Europe. Therefore, few other than priests and nobles were able to pay heed to the tales and motif of the winged horses. While winged bulls and winged lions, such as the Lion of Saint Mark (most famous as a symbol of Venice), became a Christian symbol of courage, the pegasi were chiefly used as a heraldic device for temporal princes.

It was a direct development of the classical perception of Pegasus as a symbol to power, majesty and acclaim, but also tempered with eloquence, dutifulness and reverie. In other words, it was a most suitable symbol for the feudal lords, as it represented several desired qualities of rulership wrapped into one.

Compared to other real and mythical creatures, though, pegasi were not as prevalent as, say, lions, griffons and eagles, all of them being more overt and aggressive symbols of strength and clout. Still, pegasi could be found in various flags and coats of arms. For instance, the symbol of Tuscany in Italy, the heartland of Etruscans, is a Pegasus salient (heraldic terminology for animal position, in this case the Pegasus is leaping with the forelegs in the air). It was derived from the pegasus on a coin made by celebrated Florentine artist Benvenuto Cellini.

Flag of Toscana Region (Tuscany)

Similarly, the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple, an Inn of Court for judges and barristers in England to attach to, bears the Pegasus on its coat of arms (Lower left quadrant below). It has an interesting origin. In the year 1561, a Christmas Festival was held in the Inner Temple. Robert Dudley, the 1st Earl of Leicester, played the role of Prince Pallaphilos of Sophie in the Revel. The Prince, in the revel, was the High Marshall Constable of the Knight Templars and the Patron of the Honourable Order of Pegasus, and he feasted and prayed with twenty-four valiant knights in his procession.

As a result of the vivid and memorable revel, the Pegasus became entwined with the Inn. From the tale, we can also ponder the reason why the Earl chose Pegasus as the sacred animal for his fictional order – it represented the ideal qualities for a pious, fair and just member of nobility. Presumably, it was also the reason why other noble families chose Pegasus as the symbol of their clans.

The Modern Pegasus

Since Renaissance and into the early Modern period, Pegasus has gradually taken on a role other than a symbol of fame and bravery – of poetry, creativity and inspiration. This transformation in popular perception was not baseless, it had its roots in classical understandings, then popularized by a clamor of returning the classical roots of European culture among the literati.

For instance, the Roman poet Ovid, in his telling of the deeds of the hero Perseus, described how Pegasus became acquainted with the Muses, goddesses of inspiration, science and arts. The nine Muses dwelled upon the spring Hippocrene in Mount Helicon, which Pegasus created by striking his hooves. The Muses, grateful for the creation of their welling abode, gathered around Pegasus and sung poems of joy and songs of praise (Ovid, Metamorphoses, 5).

Pegasus and the Muses

The relationship between the Muses and Pegasus was then expanded upon by later poets, and this prompts the celebration of pegasi as a symbol of creative inspiration in the modern times. In one later telling of Pegasus’s exploits after birth, he was said to be sent out by an offended Poseidon to check on the Muses on Mount Helicon, who were singing with such power that the seas, the river, and even Helicon itself moved towards heaven in delight. It turned out the Muses were contesting with a group of challengers named Pieredes, patronymic of nine daughters of Kimg Pieros (A singing duel of bands? Sounds familiar). When Pegasus arrived, he kicked on the summit of Mount Helicon to keep it down, and out gushed the clear spring of Hippocrene (Antoninus Liberalis, Metamorphoses, 9). The Muses then dwelled within it alongside the divine steed. The Muses were even said to be the caretaker of Pegasus, after Athena tamed him at his parentless birth, thereby strengthening the ties between him and inspiration in general. Therefore, poets and writers from the Romantic era thereafter celebrated Pegasus and winged horses even more so than their counterparts in antiquity.

As the modern era came by, pegasi are no longer the rare mythical beasts reserved for kings, or the high-minded poet’s companion. Similar to unicorns, pegasi had gradually diffused from their relatively rigid mythological background into a more abstract symbol of purity, inspiration and bravery. Therefore, it was ripe for becoming, and indeed became a mainstay in popular culture and fantasy literature. The story of Pegasus lent itself to a variety of commercial and military imageries that capitalized on the implied positive qualities.

Logo for Mobil, the predecessor of ExxonMobil, oil and gas conglomerate

Emblem of the 943d Rescue Group of US Air Force

Regarding the modern permutation in Norse mythology – Despite the fact that wings are not explicitly specified for most of the divine steeds in the Old Norse sources, some modern artists have dispensed with uncertainty, and made the choice of drawing winged horses in portrayal of Norse sagas. Undoubtedly, this artistic license has been influenced by the notion of winged pegasi. These winged depiction of Norse equines, in turn, reinforced the popular fascination of the winged horses.

An example would be the recurring depiction of Valkyries in American comics. For example, the Marvel heroine Danielle Moonstar rides upon a winged steed, Brightwind, which she saved from being trapped in mud and barbed wires in Asgard, and in the process inadvertently becoming a Valkyrie. Another example is Brunnhilde the Valkyrie, who similarly battles on her winged horse Aragorn.

Danielle Moonstar's first encounter with Brightwind © 2016 MARVEL

Indeed, the Pegasus still looms large in modern collective memory. The second tallest bronze statue in the US after the Statue of Liberty, Pegasus and Dragon, has recently been built in Gulfstream Park, Florida. They are the world’s tallest equine and European dragon statues.

Artist (my) impression of the sculpture

… I jest, this one is the real statue:

To conclude, the developments since the early modern era have eased the transition of pegasi as mythological steeds to companions suitable for juvenile and children works. Writers may freely incorporate the winged horse motif into their writing without necessarily explicitly alluding to Pegasus the divine steed, and yet the desired qualities still seeped through the age.

Pegasus - A persistent symbol of purity and goodness. The winged steeds, like their most famous namesake, are almost invariably the ever faithful companions to those who have a heart of gold themselves. And their immaculate innocence would cement their place in many artistic and fictional works in the past and to come.

FIN

Selected References

Grimm, J. (James Steven Stallybrass Trans.) (1883). Teutonic Mythology: Translated from the Fourth Edition with Notes and Appendix by James Stallybrass. Volume II. London: George Bell and Sons.

Hutter, M. (1995). Der luwische Wettergott piḫaššašši und der griechische Pegasos. In: M. Ofitsch – Ch. Zinko (Hgg.): Studia onomastica et indogermanica, Festschrift für F. Lochner von Hüttenbach (Arbeiten aus der Abteilung „Vergleichende Sprachwissenschaft“ Graz 9). Graz: Leykam, S. 79–97

Temba – Shiriku Rodo o kakeru yume no uma / Pegasus and the Heavenly Horses: Thundering Hoofs of the Silk Road. (2008). Nara: Nara National Museum. 255p.

Finding this sort of thing is why I love this community so much. Thank for for sharing this.

This is great! Thanks for sharing, Yinglong Fuyun.

There's a story here on Fimfiction called "Longma" about - what else? - Dragon Horses, aka bat ponies. Content to mix myths, the author named the race of Sombra-style unicorns Shadavar.

4234499 4234728

Nah, I must thank you for reading! Really, I should be pelted for the three-year gap in between the Mythologia posts. Let's not let myself wait till 2019 for the next one

4235416 The story looks intriguing! And in truth, I originally planned to write more about parallels to the European unicorns in Mythologia 1, but I figure that it would be more suitable as a separate post in order to conserve the linear narrative. But then, uh... things happened... and here we are. This time I decided to pack the parallels in to avoid that kind of situation!

This time I decided to pack the parallels in to avoid that kind of situation!

It's been two years since I got your PM, and I'm finally getting around to this

Strangely, the first comment I have is that the comic panels for the Marvel example are actually from the eighties or nineties, maybe earlier, based on what I know about the evolution of Marvel's art style, so the copyright date of 2016 might be wrong.

I want to go see that now! But wow, is that far from me. I'm on the other side of the state

And once again, I enjoyed this essay of yours! It's funny that I understand some of what you're talking about more than I would have when you wrote the unicorn one (I took Art History parts one and two this past year, which helped with when you talked about Assyrians and the Etruscans). I look forward to the next one! Hopefully I won't forget about it like I did last time—although, in my defense, it was my final year of high school when you messaged me, so I was very busy at the time; and then my first year at a university...

I'm afraid I only just read this after getting your PM years ago ^.^' It was excellent as usual! Never seen such exhaustive research for ponies! Twilight would be proud haha.

Next you should do earth ponies ;)